Cliff Diving, Anyone?

Daily Pundit: September 4, 2025

The Thin Market Trap: Concentration's Ominous Shadow on Stocks

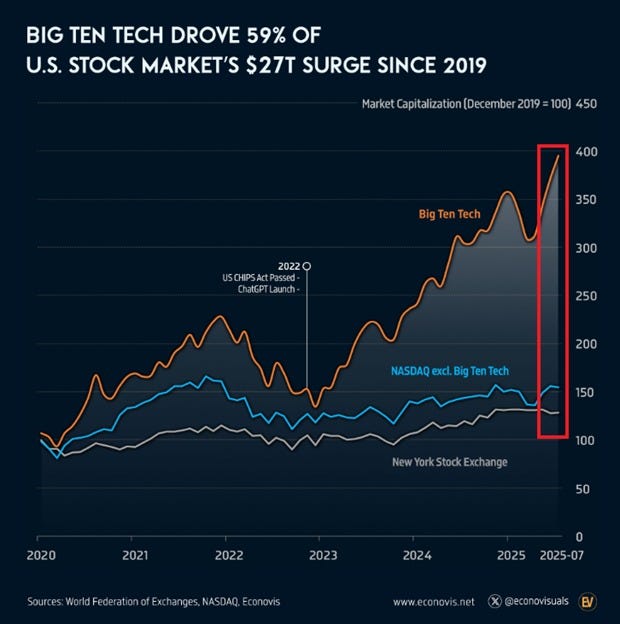

The Kobeissi Letter's chart reveals a stark reality: Big Ten Tech drove 59% of the U.S. stock market's $27T surge since 2019. The visualization shows the S&P 500's growth dominated by these giants, while the broader market lags, underscoring a concentration that has reshaped investor dynamics.

As of September 04, 2025, the stock market's landscape feels increasingly precarious, with a handful of tech behemoths carrying the weight of trillions in gains. The Kobeissi Letter's analysis captures this imbalance vividly, showing how the "Big Ten Tech" has fueled 59% of the S&P 500's $27 trillion rise since 2019. This concentration isn't just a statistic—it's a signal of vulnerability. Markets this "thin," where value clusters in a few stocks, have historically foreshadowed sharp downturns. Yet, the path forward isn't a simple repeat of the past; it's layered with new economic realities. Let's unpack the implications, drawing on history for context while acknowledging counterarguments, to gauge what this might mean for investors and the economy.

The Concentration Conundrum: A Recipe for Risk?

Market concentration occurs when a small number of stocks dominate indices, often inflating overall performance while masking underlying weaknesses. The Kobeissi chart illustrates this: since 2019, tech giants like Apple, Amazon, and Nvidia have propelled the S&P 500, but excluding them reveals a flatter trajectory for the rest. This "thin" structure reduces diversification, making the market susceptible to shocks in those key players. When sentiment shifts—due to earnings misses, regulatory scrutiny, or economic headwinds—the fallout can be swift and severe, as capital flight from concentrated holdings amplifies declines.

This isn't mere speculation; data supports the peril. Vanguard's research notes that high concentration correlates with elevated volatility, as seen in recent years where tech-heavy indices swung wildly.

The implication? A market propped by a few pillars risks crumbling if one wobbles, eroding investor confidence and liquidity. Such setups create a fragile ecosystem, where overreliance on a handful of names can lead to systemic instability, as market breadth narrows and liquidity dries up in downturns.

Historical Parallels: Echoes of Past Collapses

History offers cautionary tales where concentration preceded turmoil. The dot-com bubble of the late 1990s is a prime example: tech stocks like Cisco and Intel drove the NASDAQ's surge, but by 2000, the index plunged 78%, wiping out $5 trillion as overvalued firms collapsed.

Similarly, the Nifty Fifty era of the early 1970s saw blue-chip stocks like Xerox and Polaroid dominate, only for the 1973-74 crash to halve the S&P 500 amid inflation and oil shocks.

The 1929 Wall Street Crash followed a boom concentrated in utilities and autos, leading to an 89% Dow drop and the Great Depression.

Even the 2008 financial crisis echoed this: mortgage-backed securities concentrated risk in banks like Lehman Brothers, triggering a 57% S&P plunge.

The 1987 Black Monday crash, where the Dow fell 22.6%, was exacerbated by portfolio insurance strategies concentrating trades in a few stocks.

These examples show concentration amplifies fragility—when the leaders falter, the market follows, often abruptly within months. The dot-com bust, for instance, unfolded over 2.5 years but accelerated in 2000, losing 50% in weeks.

This pattern repeats: euphoria builds, concentration peaks, then a trigger—be it interest rates or scandals—unleashes the drop.

Voices of Dissent: Not All Concentration Spells Doom

Not everyone sees concentration as a harbinger of collapse. The Economist argues that today’s market resembles bonds more than speculative bubbles—lower valuations mean higher expected returns, mitigating crash fears.

Similarly, a Reddit theory posits that psychology drives the market upward indefinitely, with retail investors viewing dips as buys, preventing crashes.

U.S. News counters that while risks exist (e.g., high valuations), factors like stubborn inflation or jobs weakness are bigger threats than concentration alone.

These views suggest modern markets, buoyed by innovation and liquidity, might defy historical patterns. For instance, today's tech giants have stronger fundamentals than dot-com darlings, with cash flows that could weather storms. Unfortunately, “it’s different this time” has generally portray a reality intervention demonstrating precisely the opposite. This phenomenon is so common, in fact, that should you hear it, you should probably interpret it as, “Run! Run for your life!

Morningstar's 150-year crash review notes that while concentration contributed to past downturns, it's not the sole cause—external shocks like wars or recessions often ignite them.

This perspective tempers alarm, proposing that diversified indices like the S&P can absorb sector-specific hits without systemic failure.

Forward Implications: A Fragile Economy on the Brink?

If history holds, this concentration could precipitate a swift correction, eroding trillions in value and stalling growth. Tech's dominance—59% of gains since 2019—means a sector hiccup (e.g., AI slowdown) could drag the S&P, hitting retirement funds and consumer spending.

Broader economy effects include job losses in overvalued industries and reduced investment, echoing 2000's recession.

Yet, counterarguments suggest resilience—strong fundamentals in Big Tech could weather storms, with dips as buying opportunities.

Going forward, watch for Fed rate cuts or geopolitical tensions amplifying volatility. A concentrated market might exacerbate inequality, as retail investors miss out on gains tied to a few stocks, per Vanguard.

Economic slowdowns could follow, with consumer confidence dipping if portfolios crater. On the flip side, innovation from these giants might fuel recovery, as in post-dot-com advances. You could call this the “AI will save us” theory.

The key uncertainty: will diversification return, or will concentration persist, inviting a Black Swan event?

Timeline Projections: How Soon Could It Unravel?

Based on history, collapses often strike abruptly after prolonged concentration. The dot-com bubble burst in March 2000, losing 50% in months after years of tech hype.

The 1929 crash unfolded over weeks, but the lead-up spanned months of speculation.

For 2025, if parallels hold, a trigger like earnings misses could spark a 20-50% drop within 3-6 months, per Investopedia timelines.

The 1987 Black Monday plunged 22.6% in a day, following portfolio concentration.

Contravening views suggest no crash, with psychology sustaining gains.

Expect volatility, but prepare for a sudden turn. A 2008-style recession could take 12-18 months to fully unfold, but the initial drop might hit within quarters.

Today's market, with AI hype mirroring dot-com, could see a similar timeline—build-up over years, collapse in months.

Conclusion: Embracing Uncertainty

From my view, the current market situation foreshadows outcomes tougher and less predictable than any side expects, from guerrilla chaos to geopolitical shifts. It’s a call to face reality, not illusions.

Of course, anent the market, it is said that you can prevent events, or predict times, but trying to do both is a mug’s game, with the drunkardly walking market laughing at your efforts. Or, as others have noted, “Man plans, and God laughs.”

I have always been a buy and hold, high risk stock investor. I build my investments such that I could withstand a minimum 50% slide and still be okay. And I have added a lot of family to that. A 50% drop wouldn't be pleasant, but we would survive and wait for the markets to recover.

Meanwhile we work hard to own our homes and some land.

NVidia makes graphics hardware that turns out to be useful for neural nets. Back when I was job hunting on LinkedIn, I encountered multiple companies working on hardware specifically for neural nets. NVidia is powerful, but vulnerable.

Windows is increasingly unusable thanks to repeated updates of the immense .NET framework. And the Windows 10 user interface is vastly inferior to Windows 7. I dread to think of the slowdowns and privacy violations of Windows 11 with its built in AI.

Meta is over monetizing Facebook at the level of today's cable television channels. There is so much unwanted clickbait that Facebook is nearly useless as a social networking platform.

Tesla has always been ridiculously overvalued. A couple years ago I computed Tesla's market cap with the total of all the major car manufacturers that do business in the US. (I missed some Russian, Indian, and Chinese manufacturers.) Tesla was worth more than all of them combined. And now Glenn Beck's sidekicks are reporting that Tesla is doing a ridiculous bait and switch with its leasing program for used Teslas. The advertised price is about a quarter of the price that you get to see after putting down a $2500 deposit. Expect the mother of class action lawsuits.

Google is no longer the best search engine. Brave is far better. Google still has some excellent products such as maps. YouTube has immense amounts of interesting content, but the number of ads grows annoying.