The problem is that even after two generations, more or less, of an ever-growing cult of safetyism, we’ve ended up with a populace that has largely lost a healthy sense of fear. Fear serves a purpose at the individual, social, political, and cultural levels. It is an inherent part of, and reinforcer of, our survival mechanisms on all these levels.

What is Fear? | What Causes Fear? | Paul Ekman Group

Fear is one of the seven universal emotions experienced by everyone around the world. Fear arises with the threat of harm, either physical, emotional, or psychological, real or imagined. While traditionally considered a “negative” emotion, fear actually serves an important role in keeping us safe as it mobilizes us to cope with potential danger.

It would seem a truism that in order to become aware of, and then properly respond to, danger, one would first need to fear it. It is said that true bravery involves overcoming fear in order to meet danger, rather than feeling no fear at all. It is further noted that armies tend to recruit young males who are not experienced enough to fear things they should fear, a debility complicated by a natural tendency of the young to believe in their own immortality. Death, except in rare circumstances, is not generally a major concern among those who have not yet reached their majority. Which is why they can be thrown en masse into the cannons’ mouths by old men who do fear death, and with good reason. Experience has taught them that death comes to everyone, but their eternal prayer is the same one St. Augustine muttered to himself: “But not yet!”

Fear can, of course, be overdone to the point that it disables the ability to respond to the causes of it. “The boy who cried wolf” is a parable that remarks on one aspect of this, where a fear stimulus is repeatedly introduced, until it no longer produces the actual emotion. The object of the stimulus has become desensitized to it via repetition. Another aspect is the sort of fear that is so overpowering it freezes the system and disables the ability to respond to the cause of the fear in the first place. In both cases the most beneficial aspect of fear, that it “serves an important role in keeping us safe as it mobilizes us to cope with potential danger,” is short-circuited, defeating the role it should play as a survival mechanism.

Frank Herbert’s iconic masterpiece Dune places the correct (in his view) human response to fear at the heart of the work, with the famous line “Fear is the mind killer.”

The Bene Gesserit Litany Against Fear:

I must not fear.

Fear is the mind-killer.

Fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration

I will face my fear.

I will permit it to pass over me and through me.

And when it has gone past I will turn the inner eye to see its path.

Where the fear has gone there will be nothing.

Only I will remain.

Dr. Alison Escalante elaborates on this notion:

Why Dune’s Litany Against Fear Is Good Psychological Advice

Fear starts in the amygdala which rapidly signals danger to the rest of the body, initiating the fight or flight response. In humans, our higher cognitive brain can modulate that fear based on what we’ve learned. That’s why we can enjoy fear from an amusement park haunted house. But real fear or facing life-threat has a way of shutting down our higher cognitive brain as the fight-or-flight response takes over. The brain becomes flooded by fear; the prefrontal cortex goes quiet and incapable of strategic or complex thinking.

That kind of fear can realistically be understood as a “mind-killer” because it shuts down our mind’s ability to think. Under fear’s influence, we actually default back to a more animal response than a human one.

I will face my fear. I will permit it to pass over me and through me.

Few themes in modern psychology and neuroscience over the last decade have been more prominent than this: that avoiding negative emotions tends to make them stronger. This is particularly true with anxiety and fear, where several important therapies are based around helping people tolerate exposure to their fear in order to gradually lessen it.

In fact, research in positive psychology and the science of happiness find that sitting with our negative emotions tends to lessen them. And that actually makes us happier. Facing our fear is the way to go, but not if it floods us and triggers the “mind-killer” response.

That’s why permitting fear to pass over us and through us is key. This mindfulness-based action reminds us that we are separate from our fear: we can observe our fear and let is pass us by. We can experience it without being damaged by it.

Unfortunately, fear can be used by experts who understand how to create and manage its effects to manipulate entire populations. We saw this recently with the response to the Covid Pandemic, which was the outcome of a deliberately fostered mass hysteria where a significant fraction of the global population responded to a mild threat like dumb animals, once panic had turned off their ability to use their higher mental functions to control their responses. Fear killed the mass mind.

We are seeing it again in the calculated stoking of false fears about Russia and China, with much of the Western populations again turning off their rational faculties in favor of panic and hysteria. One can spark endless debates about why this sort of fear is being so assiduously stoked but suffice to say that the result is malign. Fear is being used to kill the mass mind. Again.

We must, however, never lose sight of the beneficial aspects of fear, primarily its role in human survival at all levels. It’s simple enough. Experience something that frightens you. The fear tells you that thing is dangerous. Use your higher rationality to evaluate your danger/fear reaction, and then take the most effective action in response you can to maximize the chances of your own survival. What we should seek, as individuals and as a society, is a Goldilocks approach: Too much fear kills the mind and reduces chances of survival. Too little fear can kill the body, which defeats the survival mechanism entirely. We want the middle, where fear functions to enhance and optimize our chances of surviving legitimate sources of danger.

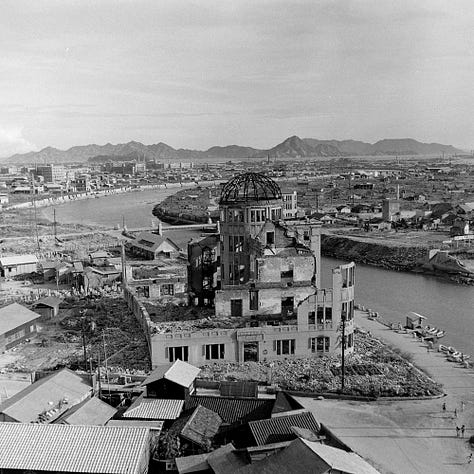

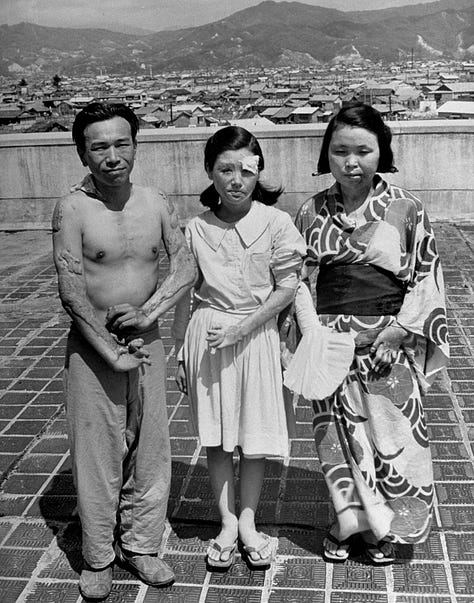

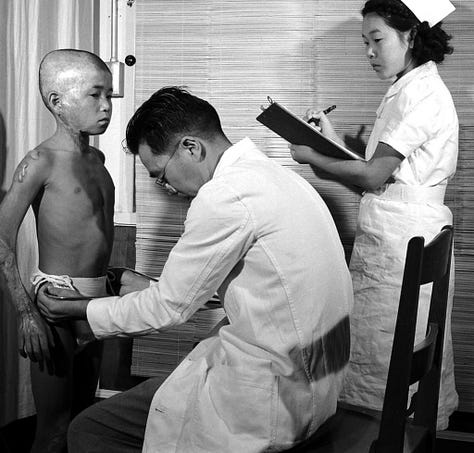

I was born on May 30, 1946, almost nine months to the day after World War II ended with the nuclear catastrophes at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I have very early memories of seeing pictures like these in the pervasive periodicals of the day, like Time and Life magazines. My dad was a magazine collector. Opened copies of Life Magazine were a fixture at my house.

That young boy was probably somewhat near my own age at that time, or at least I would have thought so had I seen that picture back then. I saw similar photos in other publications. But the real stuff of my nightmares was the video of the Hiroshima bombing, which kept turning up for years afterwards, starting with the MovieTone news pieces that accompanied visits to the theaters.

That vision of a plane banking hard away from an ever-growing ball of white fire haunted my dreams for years. And, of course, the fear was reinforced in other ways as well.

“The bomb can explode anywhere at any time.”

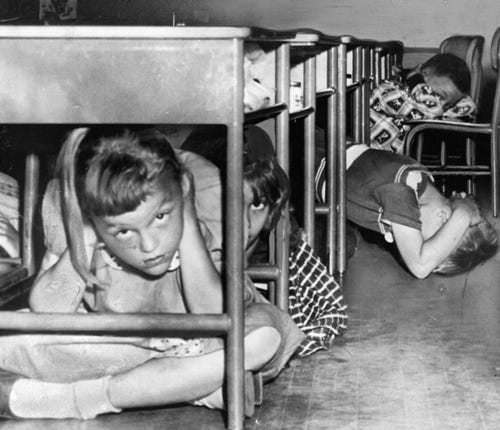

If you think that message - that death from the sky can come at any time and anyplace, to anybody including yourself - didn’t mark the kids of my generation, well, you’ve never been on the receiving end of such messaging. Nor was this an attempt to impose a terrifying hysteria on Americans, especially kids, at the time. The authorities knew there was little or nothing they could do to protect Americans caught at ground zero of a nuclear explosion. The entire duck and cover program served, first, to give such people a (spurious) sense of agency, that by doing these things they could mitigate the effects of a nuclear sunrise in their neighborhood. And to a certain extent that was correct. It was better to be in a fallout shelter underground than otherwise should the balloon go up. But ducking under your little desk at your elementary school was highly unlikely to save your ass, and all of us knew it.

What you’re looking at isn’t kids playing a fun game. You're looking at kids experiencing sheer terror. And the front half of my generation grew up with that terror.

Then along came MAD.

Mutual assured destruction - Wikipedia

Mutual assured destruction (MAD) is a doctrine of military strategy and national security policy which posits that a full-scale use of nuclear weapons by an attacker on a nuclear-armed defender with second-strike capabilities would cause the complete annihilation of both the attacker and the defender.[1] It is based on the theory of rational deterrence, which holds that the threat of using strong weapons against the enemy prevents the enemy's use of those same weapons. The strategy is a form of Nash equilibrium in which, once armed, neither side has any incentive to initiate a conflict or to disarm.

The term "mutual assured destruction", commonly abbreviated "MAD", was coined by Donald Brennan, a strategist working in Herman Kahn's Hudson Institute in 1962.[2] However, Brennan came up with this acronym ironically, spelling out the English word "mad" to argue that holding weapons capable of destroying society was irrational.[3]

Much of military conflict is in large part irrational, or at least fueled by a lack of rationality about issues and outcomes. However, that seems to have very little to do with actually preventing wars. This was something new, however, and it didn’t take long for it to be tested.

Cuban Missile Crisis - Causes, Timeline & Significance - HISTORY

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, leaders of the U.S. and the Soviet Union engaged in a tense, 13-day political and military standoff in October 1962 over the installation of nuclear-armed Soviet missiles on Cuba, just 90 miles from U.S. shores.

In a TV address on October 22, 1962, President John F. Kennedy (1917-63) notified Americans about the presence of the missiles, explained his decision to enact a naval blockade around Cuba and made it clear the U.S. was prepared to use military force if necessary to neutralize this perceived threat to national security.

Following this news, many people feared the world was on the brink of nuclear war. However, disaster was avoided when the U.S. agreed to Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s (1894-1971) offer to remove the Cuban missiles in exchange for the U.S. promising not to invade Cuba. Kennedy also secretly agreed to remove U.S. missiles from Turkey.

I was sixteen in 1962, and once again my generation, and our parents, got a real-world reminder about how close we all danced to the nuclear rainbow. What tenuous serenity we’d managed to foster since the onset of the Age of Nuclear Mass Destruction was ripped away bu the Cuban Missile Crisis as a scab is ripped from a wound festering beneath it.

Still, MAD seemed to have worked, and the two nuclear Cold Warriors backed away from the doomsday precipice. At any rate, my generation soon had a different sort of event to distract us from our long-internalized fears of atomic vaporization - personal death in the meat-grinders of Vietnam. And by the time that finally wound down in the mid 1970s, the fears of nuclear holocaust had receded even further, given that we had fought the Commie proxies in Vietnam for a decade in a very hot war that, nonetheless, never went nuclear hot.

Unfortunately, this result may have taught many a very risky lesson, that proxy wars between nuclear powers could be waged without inevitably blowing up the world. This might be true, but every test of the premise seems like one more trigger pull in a game of international Russian roulette.

By 1983, as we left the Nixon/Ford era and entered the Reagan dawn, the nuclear night terrors seemed to have mostly died down. In fact, they had subsided to the point that Reagan himself felt confident in beginning a massive re-armament program, complete with a symphony of rattling sabers. His goal was the destruction of the Communist U.S.S.R., a goal of which the leadership of the U.S.S.R. was most certainly aware. Yet, while both sides still sat on massive stockpiles of nuclear weapons, MAD seemed to function as intended.

People grew complacent. It was time for a wake-up call.

Almost forty years after a nuclear sun first bloomed over Japan, a small group of film makers thought that we had perhaps become a little too complacent and decided to do something about it.

The Day After was the idea of ABC Motion Picture Division President Brandon Stoddard,[7] who, after watching The China Syndrome, was so impressed that he envisioned creating a film exploring the effects of nuclear war on the United States. Stoddard asked his executive vice president of television movies and miniseries, Stu Samuels, to develop a script. Samuels created the title The Day After to emphasize that the story was about not a nuclear war itself but the aftermath.

The film had a rocky development period, primarily due to battles with network censors and, eventually, the U.S. Department of Defense, who demanded that the movie have the Soviets firing first, while the director, Nicholas Meyer, explicitly refused to have the film make the initiators clear. My hunch is that he felt doing so would turn it into a propaganda effort for one side or the other, and he wanted to demonize the whole concept of nuclear war, not just an enemy of one sort or another.

Meyer himself was an interesting character. He was just coming off a triumph with Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, where he is credited with not only saving the film, (by rewriting the script which most early reviewers disliked) in only twelve days, but very possibly saving the franchise as well. Although college-trained for the theater, his first big success was as the author of The Seven Percent Solution, which gave him entry to Hollywood via writing the Academy Award-nominated screenplay for the film. He was initially reluctant to take on The Day After, but after reading the script, decided to do so.

The more he learned about the concept, the more deeply he found himself affected by it.

Meyer plunged into several months of nuclear research, which made him quite pessimistic about the future, to the point of becoming ill each evening when he came home from work.

I had the same experience with the research on my own novel Lightning Fall. The more I learned about the effects of a significant EMP (Electro-Magnetic Pulse) attack on the United States, the more depressing the scenario became. The near-total lack of preparation on the part of any of our institutions to face such an attack, coupled with the horrific effects of such, painted a truly bleak picture that has never really left me. Oddly, The Day After even has such a weapon being used in the war it portrays.

Here’s an example of the sort of thing both Meyer and I ran across.

While in Kansas City, Meyer and Papazian toured the Federal Emergency Management Agency offices in Kansas City. When asked about its plans for surviving nuclear war, a FEMA official replied that it was experimenting with putting evacuation instructions in telephone books in New England. "In about six years, everyone should have them." That meeting led Meyer to later refer to FEMA as "a complete joke."

In my case, I became, and remain, convinced that in terms of surviving an EMP attack, our government and our corporations are complete jokes in nearly every possible way. I sometimes think that one characteristic of people in power is that they cannot imagine a scenario that would leave them without power in such an all-encompassing way, by which I mean not that they have been removed as individuals from their seats of power, but that anything they might have power over has been destroyed. Hitler could not have imagined that launching an invasion of the Soviet Union would result in Russian tanks parked in the rubble of the Reich’s government buildings in Berlin. I suspect this is a blind spot most leaders have.

The Day After debuted on Sunday, November 20, 1983, after an extensive ad and PR campaign where much emphasis was given to the bleak seriousness of the story. Parents were warned to watch it with their children, and booklets were handed out for discussion purposes.

Over 100 million people in 30 million households watched the film.

ABC and local TV affiliates opened 1-800 hotlines with counselors standing by. There were no commercial breaks after the nuclear attack scenes. ABC then aired a live debate on Viewpoint, ABC's occasional discussion program hosted by Nightline's Ted Koppel, featuring the scientist Carl Sagan, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, Elie Wiesel, former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, General Brent Scowcroft, and the commentator William F. Buckley Jr. Sagan argued against nuclear proliferation, but Buckley promoted the concept of nuclear deterrence. Sagan described the arms race in the following terms: "Imagine a room awash in gasoline, and there are two implacable enemies in that room. One of them has nine thousand matches, the other seven thousand matches. Each of them is concerned about who's ahead, who's stronger."[17]

The proliferation versus deterrence debate rages on into the present day, and while both sides have valid points, neither has succeeded in removing the reality of just what a full-blown nuclear exchange between the United States, and either China or Russia would mean for the average American citizen. Unfortunately, what has lessened that fear, which is a healthy reaction to the real possibility of a nuclear wasteland, is time. In America, Generation X, which had no visceral memories of Hiroshima, was approaching adulthood. Vietnam, the last war to affect Americans on a mass scale, was nearly ten years gone. And President Ronald Reagan, enjoying a booming economy after killing the stagflation monster of the 1970s, was preparing for his triumphal march to reelection after the celebratory Morning In America campaign.

Nuclear war? What nuclear war? America was back, baby! Then The Day After crashed the party, about as welcome as a cockroach on a wedding cake.

…President Ronald Reagan screened the film at Camp David (he and Nancy were avid movie buffs), and it had an effect on him. In his diary, he wrote that “The Day After” “left me greatly depressed,” and given that Reagan, in his second term, worked with the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev to put the brakes on the nuclear arms race, “Television Event” suggests, with some justification, that this may have been one instance in which a simple TV-movie nudged an American president in the right direction. (The film must have spoken to him more than Prince’s “Ronnie, Talk to Russia.”) The documentary presents “The Day After” as a primal piece of popular culture that gave the entire nation a badly needed wake-up call.

And that’s certainly one way to look at it. A hundred million people saw “The Day After” (it’s almost impossible to imagine that kind of unified television audience today), and many were shaken by it, because how could you not be? The film’s defining sequence, in which a mushroom cloud rises up over the Kansas wilderness and people get singed into X-rays (the movie’s way of depicting the fact that they’re being vaporized), exerted a primal shock and awe. “Television Event” hails “The Day After” as the rare case of a TV network not just pushing the envelope but bursting it, making the rare TV-movie that shook people to their souls.

Film critic Glenn Erickson’s excellent review also takes extensive notice of this effect.

The Day After accomplishes its goal of demonstrating that nuclear war would at the very least deprive us of our semi-civilized existence. As the personalities of vital, caring people disintegrate, we wonder if those instantly vaporized were luckier than the survivors. Robards, Guttenberg, Lori Lethin and William Allen Young succumb to horrid radiation effects. The show gives viewers four minutes of violent attack scenes, and then another hour of people we care about suffering in their homes, trying to give aid to others, or drifting on the roads soaking up radiation from the nuclear fallout.

Apparently not only President Reagan was moved by what the film portrayed.

The film was also screened for the Joint Chiefs of Staff. A government advisor who attended the screening, a friend of Meyer, told him: "If you wanted to draw blood, you did it. Those guys sat there like they were turned to stone."

Given that these were the men charged with carrying out nuclear attacks against our enemies in defense of the American people, I should hope to hell they did. It’s one thing to push a button or issue a command. It’s quite another to see and feel the results of those actions.

At one time, mostly during my childhood and youth, most Americans, and their leaders, had a gut-level appreciation for the realities of mass industrial warfare, and of the nuclear variety in particular. But we are now almost forty years down the road from the release of The Day After, and nearly eighty from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Two more generations are rising, the Millennials and Generation Z, both of which have almost no real understanding of such things beyond that gleaned from an occasional movie like Terminator II, which is mostly viewed by them as a CGI effect, not something having to do with their own world.

The Greatest Generation is dead, and my own Boomer generation is slow-walking toward the grave. Meanwhile, Russia has over 6000 nuclear warheads, we have a few hundred less, and even puny North Korea, which not more than a few years ago had none, now has fifty.

More problematic for the strategy that has contributed to keeping the nuclear peace since 1945, MAD, is that the US arsenal is sadly out of date, while Russia has just completed a decade-long replacement, refurbishment, and expansion of its nuclear stockpile, with new or refurbished warheads, classes of delivery systems, particularly hypersonic missiles of several different categories, as well as undersea and other innovations. The reason this is a problem is that middle word, “assured.” If the nuclear advantage should shift decisively enough in one or another direction, it might be conceivable that an enemy’s ability to destroy its enemy in a second strike response could be eliminated. Which would actually encourage an attack before the enemy could catch up. It should also be noted that FEMA is still a joke, the US Civil Defense program is essentially non-existent, while Russia has been expanding its Civil Defense efforts.

In the latest reflection of the Kremlin’s expanding war effort, bomb shelters across Russia are being brought back to life after more than three decades of neglect since the end of the Cold War.

State workers are quietly checking basements and other protected facilities, repairing and cleaning installations not used since the Soviet era, according to people familiar with the efforts.

The moves are part of a broader push by authorities to make sure civil-defense infrastructure is ready in case of a wider conflict, people familiar with the situation said, speaking on condition of anonymity to discuss matters that aren’t public.

The bomb-shelter drive is another example of how the invasion, now in its ninth month, is triggering a broader militarization of Russian society. Kremlin officials portray the war as an existential one between Russia and the US, a characterization Washington rejects. Russian education officials this week said they would reinstate Soviet-era basic military training in schools across the country starting next year.

Washington can “reject” all it wishes, but that won’t change how Russia regards what is existential to it, and what is not. I also find it ironic that making efforts to assure the protection of your own citizens is regarded as “militarization” by the western media. That said, the combination of a weakened US arsenal, coupled with strengthened Russian nuclear capabilities and a heightened ability to protect its citizenry only further weakens the theoretical underpinnings of MAD in the first place.

Meanwhile, we are waging a proxy war with Russia in Ukraine which we keep escalating with more weapons, more manpower, more sanctions, and more threats (including the long-standing one of breaking up Russia itself). And to think that Russia itself is not wholly aware of this goal is to betray an ignorance and naivete possible only to the deliberately brainwashed, or to somebody who has no conception whatsoever of war in the real world. I have long thought that Barbara Tuchman’s magisterial The Guns of August, portraying the policies, decisions, actions, and events leading up to World War 1, could have as easily, and perhaps even more accurately, been titled A Confederacy of Dunces Meets a Circus of Clowns.

MOSCOW (AP) — A top Russian official accused the U.S. and its allies on Saturday of trying to provoke the country’s breakup and warned that such attempts could lead to doomsday.

Dmitry Medvedev, the deputy secretary of Russia’s Security Council chaired by President Vladimir Putin, warned the West that an attempt to push Russia toward collapse would amount to a “chess game with Death.”

After attending Saturday’s farewell ceremony for former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, Medvedev published a post on his messaging app channel, referring to the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union and accusing the U.S. and its allies of trying to engineer Russia’s breakup.

Accurately, in my opinion.

“Such attempts are very dangerous and mustn’t be underestimated. Those dreamers ignore a simple axiom: a forceful disintegration of a nuclear power is always a chess game with Death, in which it’s known precisely when the check and mate comes: doomsday for mankind.”

The only way to win that chess game is to not play in the first place. But Americans, even at the highest of levels, seem to think they have nothing to fear from the game. It seems to arouse in them no fears for their own survival, no understanding of the perils involved, no comprehension that a perfectly plausible outcome could easily be the horrible deaths of themselves, their families, and everything else they hold dear.

We need that healthy fear again. We need another wake-up call like The Day After. If we are hell-bent on this, we all need to understand just what we are risking. We need to understand the downside, as well as the upside.

Meanwhile, yesterday, this:

Russian President Vladimir Putin said he is suspending his country’s participation in the New START nuclear arms reduction treaty with the United States, imperiling the last remaining pact that regulates the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals.

If you’d like a refresher course, or, for my younger readers, a primer on just what sort of game we are playing, you can watch The Day After on YouTube. Or just stay right here.