Consider for a moment some of the more unsettling facts about American governance at its highest level. Let's start with the House of Representatives. Here is what a fresh, green, incoming Congressman is told by his mentors in his first few days in office.

Incoming lawmakers are instructed to spend upwards of four hours per day raising money, which is time taken away from the legislative responsibilities of being an elected official. Many members will explain, however, that fundraising is a sacrifice that makes the rest of their work possible.

“Per day” is a somewhat elastic term, given that Congressional work schedules are not necessarily congruent with work schedules in the real world.

An individual Member’s schedule is extremely hectic when he or she is in Washington. There are dozens of different issues and commitments pulling them in different directions daily with the goal of packing in as much as possible in less than three working days. It is a real challenge to find enough time to meet with constituents, manage and direct staff, review constituent input, attend hearings and events, read and review policy issues and bills, respond to media, fundraise, keep in touch with one’s family, and still have time to eat and sleep. A member’s day in Washington often starts at 6 am and doesn’t end until 9 or 10 pm at night; in addition, there is preparation for the next day. These members then hurriedly scramble for a flight out of D.C. on Thursday to do series of meetings, events, and visits in their districts on Friday and the weekend. Then, they are back on a late afternoon Monday or Tuesday morning flight to Washington to return to the same rapid pace and erratic schedule.

And those three formal workdays don't take into account the actual number of days a member is expected to be at least with shouting distance of his office or the chamber.

Note the variances. It is obvious that the first year of a congress tends to be in session more than the second. The reason should be obvious. Every two years, every single member of the House of Representatives must go out and face the verdict of the voters in an election. Election years require a congressman to spend a lot more money than non-election years, and that means a lot more time spent fundraising, and a lot less time doing the people's business. Or giving the people the business, depending on how you view the matter.

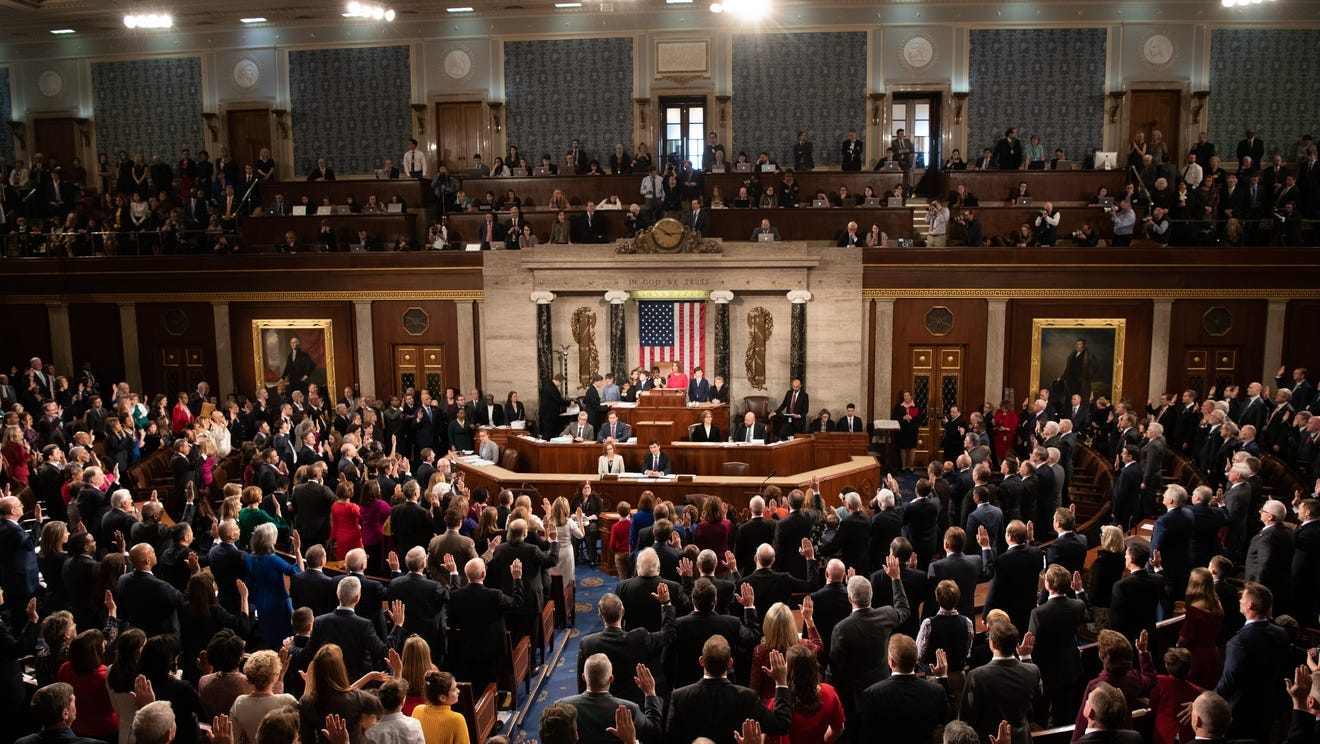

What the average person thinks the House of Representatives looks like.

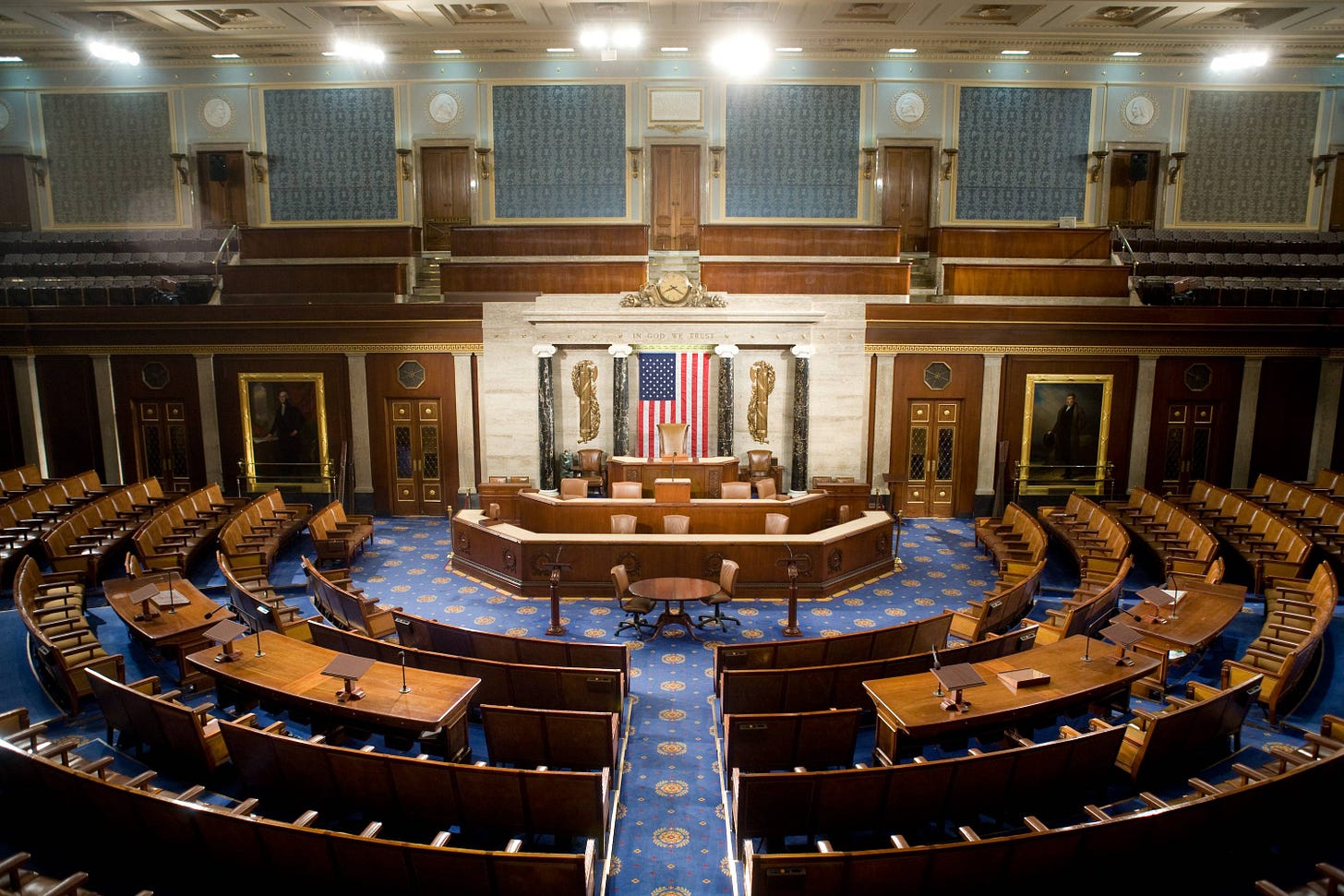

What the House of Representatives looks like most of the time.

So, what, exactly, do these Congressional E-tickets to the “People’s House” actually cost our intrepid Representatives? (For Millennials and Zoomers: Wikipedia informs us that “an E ticket (officially an E coupon) was a type of admission ticket used at the Disneyland and Magic Kingdom theme parks before 1982, where it admitted the bearer to the newest, most advanced, or popular rides and attractions).

It can vary considerably, but even the cheapest version is…quite a lot.

The median amount of money raised between July and September by a member of the House of Representatives running for reelection in 2022 was $209,000 — or about $2,300 per day. Meanwhile, the median amount raised by a freshman House member was $278,000 — or about $3,000 per day. The typical House incumbent running for reelection in a race they won by less than 5 percentage points in 2020 raised roughly $601,000 during the third quarter — about $6,500 per day, or nearly three times as much money as the typical House member.

You might note - and wonder about - the fact that a first term freshman raises about $700 per day more than the vet running for reelection. The reason is simple. The most critical election for a congressman will almost always be his first try at reelection. If he can successfully surmount that hurdle, he will probably settle into the desirable status of permanent incumbent - and keep in mind that the turnover rate in Congress is somewhat less than that of the old Soviet Politburo. A secondary factor is that any campaign funds not spent can be rolled over for the next election. And if you can become one of those guys “who can only be defeated if he’s caught in bed with a live boy or a dead girl,” all the better. That Representative won’t have to worry much about spending on his own campaign and can concentrate on growing his kitty to lion and tiger dimensions. When it comes to things like that, bigger is always better.

But why bother with the fundraising grind if you don’t need to? Two reasons. The first is that you can take it with you when you retire. The second is that you can use that money to buy power and influence in the House of Representatives itself. (The same goes for the Senate, although on a much larger scale: See Mitch McConnel’s private pocketbook, the Senate Leadership Fund SuperPAC, below.

That is nuclear-level financial throw-weight, and anybody who understood what it meant knew perfectly well that Trumpian efforts to primary Mitch in 2020 would die still-born (as they did). The SLF says it exists to elect Republicans to the Senate, but it can put its money wherever it likes, including into local and statewide races in Kentucky, McConnell’s home state. Further, anybody who thinks that Mitch will ever leave the Senate Majority or Minority Leader position against his will, given how much money the SLF has contributed to the reelections of sitting Senate members, simply doesn’t understand how these things work.

The House is no different, of course. Speaker Kevin McCarthy was never in any danger of losing his position to the ragged gang of dissidents who tied up the House for a few days recently, for two reasons. The first was his own campaign PAC, which donated to just about every Republican running for reelection, including most of those who “revolted” against him. The second was his relationship with the Congressional Leadership SuperPAC, quite similar to McConnell’s with his Senate Leadership SuperPAC. How much money did the CLF spread around in 2022? This much.

That’s right. Congressional Republicans had McCarthy to thank for nearly a quarter billion dollars in campaign funding during a campaign that turned out to be considerably more hard-fought than most expected. That is a lot of influence, and, while the CLF isn’t McCarthy’s personal piggy bank, he was responsible for much of the money that flowed into it, and then out of it into the campaigns of his fellow Congressmen. It is unsurprising that nobody was much interested in derailing that gravy train by turning it over to some untested and mostly unknown “dissident.” It is also why one of, if not the, most important qualifications for achieving a position of power in Congress is the ability to raise lots and lots of money. Kevin McCarthy is an extremely proficient fund raiser, which is why he is Speaker of the House today.

Having established that our Representatives in “The People's House” are trained from their Congressional cradles - you might even say groomed from the cradle - to pimp themselves out for financial contributions, let us move on to the perennial complaint about too much money in politics. Well, yes. But most protesters never get past some sort of simplistic blame game aimed at the donors rather than the recipients, because they never understand that the problem is the nature of the game itself.

The Players of the Game

If prostitution/pimpery is the oldest profession, and politics the second oldest, the two meet in a glorious melding of mutual interest in our campaign finance system, which is really our political finance system. It is a game created by politicians (primarily) at the behest of donors in order to serve the dual purpose of financing the political careers of the pols and providing a way for major financial entities to exert significant amounts of pressure on legislative and regulatory processes for their own benefit. It is also a game that either side could end on a moment's notice, but neither side will do so of its own volition, because the benefits to both sides are so great.

It is also necessary to understand the difference between small donors, usually characterized as making donations under $200 dollars, and large donors, who donate more. It is not unusual to see some politicians raise more money from small donors than large ones, and yet it will still be the large donors who call most of the political shots. The reason for this is that large donor fundraising tends to be retail in nature, ie. one on one, while small donor fundraising is more a matter of wholesale mass communications, which are almost entirely impersonal, at least as far as the individual politician is concerned. There is also the issue of donor motivation. Small donors are signaling a somewhat amorphous approval of a politician, along the lines of “I like what you’re doing, so here’s a hundred bucks,” while large donors are seeking specific actions that benefit themselves in a specific way. “Our organization needs a carve-out in IRS regulations that exempts products from our new solar panel factory in Brazil from import duties here in the US, and by the way, here’s a hundred grand for your SuperPAC, okay?”

In 2021, there were over 12,000 registered lobbyists working to influence our political leaders in Washington, and they “contributed” $3.78 billion (adjusted for inflation) in the cause of making sure government paid very close attention and much deference to their own interests, which are not in any way to be confused with either the national interests, or the interests of the American people. Often times quite the opposite, in fact.

The Financialization of American Governance

The term “financialization” is usually tossed around in the media as a somewhat vague explanation of what happens when some gigantic bank or investment corporation makes a lot of bets on an arcane financial instrument, and them makes bets on those bets in an ever more convoluted daisy chain that never achieves public notice unless or until it blows up and takes down the bettors or the financial system itself, as nearly occurred in the so-called “Housing Crash” of 2007-2008. (Which was really a bank and investment house crash).

But the term properly has a more general meaning.

Financialisation: A Primer

What is financialization and why is it important?

Financialization is a relatively new term, which covers such a range of phenomena that it is difficult to define precisely. The most-cited definition, from Gerald Epstein, states: “financialization means the increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of the domestic and international economies”1.

It is a process in which financial intermediaries and technologies have gained unprecedented influence over our daily lives.

The expansion of financial markets is not only about the volume of financial trading, but also the increasing diversity of transactions and market players and their intersection with all parts of economy and society. In short, financialization must be understood as a radical transformation within the financial sector that has altered entire economies – from the household and the firm to the functioning of monetary systems and commodity markets.

Research has shown that financialization has increased inequality, slowed down investment in ‘real’ production, mounted pressures on indebted households and individuals, and led to a decline in democratic accountability.

Modern observers have been making of late a somewhat fatuous analysis to the effect that “politics is downstream from culture,” but this isn’t true at all. Most politics is downstream from money. Instinctively, we know this. Wheezes like, “Money talks, bullshit walks,” “cash is king,” “the golden rule - those who have the gold rule,” “cash on the barrelhead only,” and a host of others became cliches not because they were incorrect, but because they were accurate. But along with these truisms rose others regarded as equally true. Carl Sandburg summarized their gist in one powerful sentence. “Money is power, freedom, a cushion, the root of all evil, the sum of blessings.”

Money makes the (political) world go round. Money in politics also makes big donors richer, (they hope) and it certainly makes politicians richer.

The leaders of both chambers make the top 10 list. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) has seen her wealth increase to nearly $115 million from $41 million in 2004, the first year OpenSecrets began tracking personal finances. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) saw his net worth increase from $3 million to over $34 million during that time. Both political leaders are married to affluent individuals who are driving those increases.

Open Secrets doesn’t go into the matter of how those affluent family members continued to grow their affluence while married to the very definition of insider financial knowledge, members of Congress.

While it is true that politics on the national level has become, for the most part, a rich man’s game, and therefore many freshmen Congressmen are wealthy in their own right, almost none of them end up poorer over the period of their service, and more than a few become a lot richer.

With this in mind, let’s return to that broad definition of financialization - “financialization means the increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of the domestic and international economies.”

While generally accurate, this glosses over the fact that the domestic economy is almost entirely governed by Congress and the Executive. Only Congress is constitutionally granted the power to:

…lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States;

To borrow Money on the credit of the United States;

To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes;

To establish a uniform Rule of Naturalization, and uniform Laws on the subject of Bankruptcies throughout the United States;

To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures;

To provide for the Punishment of counterfeiting the Securities and current Coin of the United States;

In essence, Congress is empowered to raise, borrow, coin, and regulate money both domestic and foreign. It is not entirely incorrect to say that Congress is the American economy, or at least the primary progenitor of it. Hence financial “motives, markets, actors, and institutions” have come to control the doings of Congress almost entirely. And keep in mind that the Federal Reserve is entirely a creature of Congress, having been created by it in 1913, and remains accountable to Congress today.

I’ve concentrated mostly on the House of Representatives as an example of the problem of the financialization of American politics and governance, but the phenomenon is being carried out across the entire political and governmental spectrum, from the bottom to the top. “We the people” have become irrelevant in our own house because of it. We like to console ourselves that we still have ultimate control over our destinies which we exercise via our votes at election time, but the inaccuracy of that proposition is becoming ever more apparent as financialization continues to permeate our politics, our governance, and every aspect of our daily lives.

In the end, this financialization has been carried out through pervasive and complicated mechanisms of bribery, where vast sums of money are traded for favors that guarantee vast sums of money for those doing the bribing. The term for that is corruption, and today’s America reeks of it. Our politicians are groomed from the very beginning to accept this situation as normal, as “just the way things are,” and to participate fully in it by spending much of their time soliciting bribes, (“dialing for dollars,” as it is drolly called) a task which makes those who desire to offer bribes for favors very happy.

A nation that sells everything will eventually sell its soul, and, sad to say, America has probably already done this. What could be more soulless than fomenting a war in Ukraine so that a totally corrupted President can hide the evidence of his corruption there, and so that a gigantic financial corporation like Black Rock can set itself up to rape what remains after the war ends?

So, then, what to do?

The answer to that is simple, obvious, and straightforward. First, every election at every level must be financed solely by public funding. That means no financial campaign input from any other source of any kind whatsoever, including a candidate’s own personal wealth. Second, any government functionary of any sort who solicits or accepts such funding should be charged with a felony and, if convicted, permanently barred from any sort of government service henceforth, in addition to whatever other criminal penalties are imposed. Third, any entity offering such bribes should also be charged with a felony for each offense and, if convicted, lose its license, (if incorporated) to operate as a corporation.

The last is of paramount importance, because the Framers never intended that corporations should have been able to assume the outsized powers they’ve gained over the years and enjoy today. Originally, corporations were relatively puny things, created to accomplish certain objectives, and designed to be dissolved upon accomplishing them.

What the Founding Fathers Really Thought About Corporations (hbr.org)

Americans inherited the legal form of the corporation from Britain, where it was bestowed as a royal privilege on certain institutions or, more often, used to organize municipal governments. Just after the Revolution, new state legislators had to decide what to do about these charters. They could abolish them entirely, or find a way to democratize them and make them compatible with the spirit of independence and the structure of the federal republic. They chose the latter. So the first American corporations end up being cities and schools, along with some charitable organizations.

We don’t really begin to see economic enterprises chartered as corporations until the 1790s. Some are banks, others are companies that were going to build canals, turnpikes, and bridges — infrastructure projects that states did not have the money to build themselves. Citizens petitioned legislators for a corporate charter, and if a critical mass of political pressure could build in a capital, they got an act of incorporation. It specified their capitalization limitations, limited their lifespan, and dictated the boundaries of their operations and functions.

Unfortunately for both the political, economic, and moral health of the nation, corporations have, through a combination of judicial error, political calculation, and, yes, corruption, been permitted to assume a mantle of constitutional personhood, that actually legitimizes their ability to corrupt, most recently with the Citizens United decision that makes their political bribes a matter of “freedom of speech” protected by the First Amendment.

A couple months ago the Supreme Court ruled that restricting corporate political spending amounted to restricting free speech. In this view, corporations are pretty much equivalent to people. Would that have seemed reasonable to the Founding Fathers?

In a word, no.

I read this opinion carefully — I’m trained as a historian, not a lawyer. Chief Justice Roberts lays out an ideologically pure view of corporations as associations of citizens — leveling differences between companies, schools and other groups. So in his view Boeing is no different from Harvard, which is no different from the NAACP, or Citizens United, or my local neighborhood civic association. It’s lovely prose, but as a matter of history the majority is simply wrong.

Let me put it this way: the Founders did not confuse Boston’s Sons of Liberty with the British East India Company. They could distinguish among different varieties of association — and they understood that corporate personhood was a legal fiction that was limited to a courtroom. It wasn’t literal. Corporations could not vote or hold office. They held property, and to enable a shifting group of shareholders to hold that property over time and to sue and be sued in court, they were granted this fictive personhood in a limited legal context.

Early Americans had a far more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of corporations than the Court gives them credit for. They were much more comfortable with retaining pre-Revolutionary city or school charters than with creating new corporations that would concentrate economic and political power in potentially unaccountable institutions. When you read Madison in particular, you see that he wasn’t blindly hostile to banks during his fight with Alexander Hamilton over the Bank of the United States. Instead, he’s worried about the unchecked power of accumulations of capital that come with creating a class of bankers.

So even as this generation of Americans became comfortable with the idea of using the corporate form as a way to set priorities and mobilize capital, they did their best to make sure that those institutions were subordinate to elected officials and representative government. They saw corporations as corrupting influences on both the economy at large and on government — that’s why they described the East India Company as imperium in imperio, a sort of “state within a state.” This wasn’t an outcome they were looking to replicate.

The long tale of how corporations managed to achieve such “imperial” status is for another post, but a thumbnail version is this:

What changed in the interim?

Well, we have a Civil War, and to prevent former Confederate states from infringing on the rights of freed slaves, the 14th Amendment extends “equal protection” to all American citizens. Section 1 specifies that this applies to all “persons” and in an 1886 Supreme Court case involving a railroad, the court’s reporter — a former railroad president — writes a note saying that the justices agreed that a corporation qualified as a person. This isn’t in the opinion itself, and some legal historians think it’s a moot issue, but Justices William Douglas and Hugo Black later cite it as a momentous event. Either way, what’s clear is that in the late 19th century, far more equal protection cases were heard by the Supreme Court where corporations were plaintiffs than freedmen. The Court — not the legislatures or the Congress — allowed the personhood distinction to slip away.

Note the inherent corruption here. A court reporter whose interests were likely entirely corporate added his interpretation on his report of the case, which was not actually a part of the original opinion itself. (Much as Antonin Scalia’s “disastrous dicta” in the Heller Second Amendment case led to a decade and a half’s worth of erroneous jurisprudence that necessitated the Supreme Court stepping in to remedy it in Bruen last year).

Even in a much better environment than we enjoy currently, the likelihood of removing the concept of corporate personhood from our body of law is vanishingly small. Corporations themselves are embedded in every aspect of our civil and business life. But we could at least hope to establish that their spurious personhood should not provide them an inviolable shield against consequences of their own wrongdoing. If corporations are people, then those that willfully corrupt the Republic for their own ends should be subject to the death penalty. Sad to say, nothing less would be likely to deter them.

Of course, we do not live in that “better environment,” in no small part due to the corrupting influence of big finance, and the willing, and even eager, corruption of our politics. We live in a world where a couple of gigantic pharmaceutical companies can extend massive largess to politicians and administrative regulators like Anthony Fauci in order to force improperly and possibly fraudulently vetted vaccines, protected against legal recourse, on a deliberately terrified public. The potential harm of this piece of corruption is only now beginning to be tallied, but the signs are dire. If the excess death indicators turn out to be accurate, and to be due to the vaccines, then one downside to the ongoing financialization of politics and the corruption of our governance may turn out to be the biggest mass murder in American history.

How much are your liberties worth to you? You may not know exactly how to answer that question, but you can bet your bottom dollar that somewhere, somebody has figured exactly how much to sell them for, and somebody else has figured out exactly how much to pay for them.

All that is left is the dickering over price. Because we have already established what all involved actually are.

Swimming Downstream From the Culture Pool is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Free is fine, but paid is better for both of us.

This is such a great post. Our government officials are irredeemably corrupt. But they are only responding to the carrots offered and sticks wielded by our Oligarchs. Oligarchy is where the true power lies. It’s the reason for a person like Jeffrey Epstein. Currently, most of our nation’s problems can be attributed to the Oligarchs waging a war on the last bastion of ostensibly free people in the world, and their sworn enemy, the family unit of the American Middle Class; whom they are trying mightily to enslave and/or eliminate. And will give eachother humanitarian awards for their efforts.