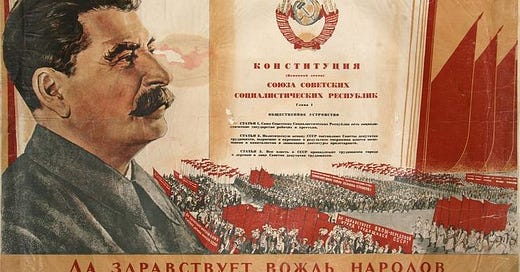

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics enjoyed three, or four, depending on how you count them, formal constitutions, but they all suffered the same problem. They were meaningless, or, rather, they had no meaning as far as real life in the Soviet Union went. They were, to use a term suddenly gaining currency these days, aspirational, although one can legitimately question who regarded them as such, and what the aspirations enshrined within them actually were.

The United States of America has had two constitutions, one, the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, in force between 1781 and 1789, when it was replaced by, two, the Constitution for the United States of America.

The first was primarily an organizational framework to provide the union of the thirteen colonies a platform from which to negotiate with potential foreign allies, and well as provide a formal means through which the colonies could aid each other in the revolutionary war against England, primarily by keeping an American military in the field, and a navy of privateers on the oceans. There was very little about the rights of individual citizens in this first constitution, beyond delegating their establishment, protection, and administration to the individual states.

This excerpt from a Wikipedia article on the Shays Rebellion, which occurred in Massachusetts under the regime of the Articles of Confederation demonstrates just how precarious the “unalienable rights” solemnly referenced in the Declaration of Independence only a decade before really were:

Governor Bowdoin commanded the legislature to "vindicate the insulted dignity of government". Samuel Adams claimed that foreigners ("British emissaries") were instigating treason among citizens. Adams helped draw up a Riot Act and a resolution suspending habeas corpus so the authorities could legally keep people in jail without trial.

Adams proposed a new legal distinction that rebellion in a republic should be punished by death.[17] The legislature also moved to make some concessions on matters that upset farmers, saying that certain old taxes could now be paid in goods instead of hard currency.[17] These measures were followed by one prohibiting speech critical of the government and offering pardons to protestors willing to take an oath of allegiance.[35] These legislative actions were unsuccessful in quelling the protests,[17] and the suspension of habeas corpus alarmed many.[36]

The rebellion was put down not long after, with only a few casualties after a confrontation at the Springfield Armory, which led to most of the most fervent revolutionaries being scattered far and wide. Three years after it ended, the participants were pardoned, and most resumed their normal lives. Nonetheless, the rebellion was a primary catalyst for the increasingly influential Federalists to call for a convention to “repair” the Articles of Confederation.

Once the convention had been convened, however, most of the participants determined that there was no fixing the Articles, and so they decided to start over, more or less from the ground up. There were two overriding schools of thought on the matter. The Federalists (who weren’t federalists at all - they were centralists who advocated for a strong central (federal) government, and the Anti-Federalists (who were - they advocated for a weaker central government in which the federation of states would occupy the heavier side of the balance of power) battled each other across an ideological divide that centered on a single question: How powerful was this new government to be? Would the states continue to maintain what they regarded as essential prerogatives and liberties, or would this new “Federal” government dominate and, potentially, oppress?

This question was paramount in the decisions made concerning almost every clause of the new constitution. Each side had the weight of history as support and reference. Oppression by the overwhelming central power invested in the King of England had led to the Rebellion and overthrow of that power in the New World by the American colonists. But the undeniable failure of the Articles of Confederation, which vested almost all power in the individual states, and almost none in a central government, also had immediate gravity in the debate.

In the end, most components of the new governing compact, from the individual articles to the addition of the Bill of Rights, resulted from compromises on both sides in order to create a final agreement. Anent the Bill of Rights, it is worth noting that the Federalists saw no need for such, given their contention that the powers of the federal government would be strictly limited to those granted to it by the Constitution itself.

The anti-federalists, on the other hand, were by no means so sanguine about the probability of the federal government remaining within the boundaries envisioned by the federalists. From their point of view, all that “blank space” beyond the constitutionally granted powers was simply a fertile field for expansionary mischief on the part of the federal government. Since the point of view of the two most powerful states, Virginia and New York, leaned anti-federalist, Madison, a federalist, changed his mind about a bill of rights and set about creating one as a set of amendments to the new constitution, after promising to do so in order to assure its passage.

The first congress held under the sway of the constitution itself was Madison’s venue for the creation of this bill of rights, and he followed the amendment procedures established in that constitution. Ten of the original twelve amendments were ratified by the requisite number of states by September of 1791, a bit more than three years after the constitution itself was ratified. The eleventh was ratified in 1992.

The cynicism demonstrated by the anti-Federalists as to the limiting effects of constitutionally enumerated powers turned out to be more than justified, given that formal efforts to expand beyond them began almost immediately. However, one must note several barn doors to a central tyranny were left standing wide open in the text of the constitution itself: The supremacy clause, the necessary and proper clause, the general welfare clause, and the commerce clause.

A writer calling himself Cincinnatius (Arthur Lee, one of the Virginia Lees so ubiquitous throughout American history) took a rhetorical sledgehammer to the contention that the constitutionally limited grant of powers to the federal government was all the protection required to guarantee the liberties of the states and the people:

If the defence you have thought proper to set up, and the explanations you have been pleased to give, should be found, upon a full and fair examination, to be fallacious or inadequate; I am not without hope, that candor, of which no gentleman talks more, will render you a convert to the opinion, that some material parts of the proposed Constitution are so constructed—that a monstrous aristocracy springing from it, must necessarily swallow up the democratic rights of the union, and sacrifice the liberties of the people to the power and domination of a few.

Your first attempt is to apologize for so very obvious a defect as—the omission of a declaration of rights. This apology consists in a very ingenious discovery; that in the state constitutions, whatever is not reserved is given; but in the congressional constitution, whatever is not given, is reserved. This has more the quaintness of a conundrum, than the dignity of an argument. The conventions that made the state and the general constitutions, sprang from the same source, were delegated for the same purpose—that is, for framing rules by which we should be governed, and ascertaining those powers which it was necessary to vest in our rulers. Where then is this distinction to be found, but in your assumption? Is it in the powers given to the members of convention? no—Is it in the constitution? not a word of it:—And yet on this play of words, this dictum of yours, this distinction without a difference, you would persuade us to rest our most essential rights. I trust, however, that the good sense of this free people cannot be so easily imposed on by professional figments. The confederation, in its very outset, declares— that what is not expressly given, is reserved. This constitution makes no such reservation. The presumption therefore is, that the framers of the proposed constitution, did not mean to subject it to the same exception.*

*The reference is to the Articles of Confederation, and is correct, in that the second article of that compact states:

Article II. Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom and independence, and every Power, Jurisdiction and right, which is not by this confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled.

It is a legitimately poignant (and effective) conclusion to wonder that the very argument being advanced by the Federalists as their primary case against the need for a bill of rights, the same argument that was enshrined in the previous constitution, was omitted from the one under debate.

Now as to those barn doors I just mentioned. In order:

The Supremacy Clause:

This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.

The Necessary and Proper Clause:

[The Congress shall have Power . . . ] To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.

The General Welfare Clause:

The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States;

The Commerce Clause:

[The Congress shall have Power . . . ] To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes; . . .

Anti-Federalist objections to the Supremacy Clause should be obvious. The central debate surrounding the new constitution was how much power over the states should be allotted to it. While few argued that the Articles of Confederation gave the central government too much power, difficulties surfaced in the debates over what constituted the correct amount of power, (and what constituted too much power).

The anti-federalists had reason to doubt the intentions of the federalists on that score, given that the “Virginia Plan,” a blueprint for a new constitution presented by Virginia Governor Randolph to the convention, but in most part inspired by the thought of James Madison, included such items as a “federal negative.”

James Madison of Virginia had suggested that the new constitution include a "federal negative," which would give Congress the authority to veto any law passed by a state legislature. He viewed this as a critical safeguard against unchecked power at the state level. In late May, Madison's Virginia delegation had presented a plan for the constitution that included a watered-down version of the negative. Now, in June, Charles Pinckney of South Carolina revived the original version, calling it "the corner stone of an efficient national Government." Not everyone agreed with Pinckney's assessment, however. Opponents charged that Madison's federal negative would allow Congress to "enslave the states" and let "large States crush the small ones."

Further cause for suspicion of Federalist motives was given by Alexander Hamilton’s unabashed preference for a monarchial structure for the new central government.

The true policy of the small States therefore lies in promoting those principles and that form of Gov[ernmen]t which will most approximate the States to the condition of counties."

6 Though he [Madison] opposed the creation of one simple republic as inexpedient and unattainable, his proposal for a negative on state laws was the means of uniting the advantages of a single enlarged republic to the existing American state system. In I787, Madison was thus scarcely less a consolidationist than Alexander Hamilton; the real difference between the two was that Hamilton unblushingly preferred a monarchy on the British model while Madison sought to establish a national government on republican principles.

This is very strong stuff of a sort you will almost never see discussed beyond specialist historical forums dedicated to Madison’s role as “Father of the Constitution.” Certainly you won’t find it in most standard American History survey courses at any level within the academy.

At any rate, Madison lost this battle on the convention floor, as well as the concomitant effort to have both houses of the legislature selected by proportional representation among the states - that is, larger states would have more weight than smaller states in the selection of both legislative houses, not just in the House of Representatives.

Needless to say, all of this was just grist for the busy mills of the anti-federalists, and did nothing to allay their fears that the Convention was heading down the road toward a centralized form of tyranny that would eliminate the individual states as anything more than rubber stamps for the actions of the federal institutions.

And it was on this turn that both sides waged, won, and lost the various battles that eventually resulted in our Constitution and its integral Bill of Rights created the year after its ratification in the first Congress governed by its rules. So how has history judged this great effort? Certain conclusions can be quickly drawn. The Centralists (Federalists) eventually emerged victorious, insofar as those four barn doors I previously mentioned ended up concentrating almost all real power in the hands of the Federal Leviathan, the Moloch on the Potomac, no matter how much smarmy nodding might be aimed in the direction of our sacred republican form of government. “This has resulted in a system of governance I characterize as totalauthoritarianism, a portmanteau word created from totalitarianism and authoritarianism. The line between these two “systems of rule” is fuzzy enough as it is. It may make more sense, especially in a post-industrial high tech world, to simply treat them as two sides of the same coin.

Encyclopedia Britannica, which I cite because the deeply corrupted Wikipedia is useless as a source for discussion on such subjects, has this to say about the ostensible differences:

Totalitarianism | Definition, Characteristics, Examples, & Facts | Britannica

Totalitarianism is a form of government that attempts to assert total control over the lives of its citizens. It is characterized by strong central rule that attempts to control and direct all aspects of individual life through coercion and repression. It does not permit individual freedom. Traditional social institutions and organizations are discouraged and suppressed, making people more willing to be merged into a single unified movement. Totalitarian states typically pursue a special goal to the exclusion of all others, with all resources directed toward its attainment, regardless of the cost.

The primary example offered is Mussolini's Fascist Italy:

Notable examples of totalitarian states include Italy under Benito Mussolini (1922–43)

“Contrasted” to:

Authoritarianism | Definition, History, Examples, & Facts | Britannica

Authoritarianism, in politics and government, the blind submission to authority and the repression of individual freedom of thought and action. Authoritarian regimes are systems of government that have no established mechanism for the transfer of executive power and do not afford their citizens civil liberties or political rights. Power is concentrated in the hands of a single leader or a small elite, whose decisions are taken without regard for the will of the people. The term authoritarianism is often used to denote any form of government that is not democratic, but studies have demonstrated that there is a great deal of variation in authoritarian rule.

Which is followed by some mushy quibbling:

Fascism is conceptually difficult to define but represents a highly militaristic and hyper-nationalistic form of rule. Fascist regimes resemble totalitarian systems in their mobilization of the public under a mass political party and their glorification of a heroic leader.

It's "difficult to define" because post-WWII narratives require it to be different in nature from other run-of-the-mill leftwing socialist systems of authoritarian governance because its version of leftwing socialist system of authoritarian governance must somehow be be characterized as rightwing.

In truth, the supposed "differences" between totalitarianism and authoritarians are primarily based on the value judgements made by those proffering various definitions of the two, said values often highly personal and subjective in nature.

Hence, totalauthoritarianism and today's U.S. system of governance, which partakes of aspects of both definitions.

Totalitarian aspects of today's America:

supplanting of all political institutions with new ones? Check.

sweeping away of all legal, social, and political traditions? Check.

pursuit some special goal, such as industrialization or conquest, to the exclusion of all others? Check.

All resources are directed toward its attainment, regardless of the cost? Check.

an ideology that explains everything in terms of the goal, rationalizing all obstacles that may arise and all forces that may contend with the state? Check.

Any dissent is branded evil, and internal political differences are not permitted? Check.

traditional social institutions and organizations are discouraged and suppressed. Thus, the social fabric is weakened and people become more amenable to absorption into a single, unified movement? Check.

Old religious and social ties are supplanted by artificial ties to the state and its ideology? Check.

Large-scale organized violence becomes permissible and sometimes necessary under totalitarian rule, justified by the overriding commitment to the state ideology and pursuit of the state’s goal? Check.

whole classes of people, such as the Jews [or white males] …are singled out for persecution and extinction? Check.

the persecuted are linked with some external enemy and blamed for the state’s troubles? Check

Authoritarian aspects of today’s America:

led by a single political “ruling” party? Check.

regime evolving into totalitarian system that exercises total control over society? Check.

authoritarian [phony] populist leadership? Check.

uses anti-elitist and highly divisive nativist rhetoric to garner political support? Check.

leader uses this support as a pretext to undermine democratic institutions? Check.

leaders rise to power through elections but then deliberately create direct linkages with the public at the expense of other national institutions? Check.

directly connecting with and distributing goods to their supporters, populist leaders cause such institutions to decay? Check.

parties are no longer able to make people feel as though their voices are being heard? Check.

elites appear too removed from society, and citizens search for authoritarian alternatives that promise to directly and quickly solve all of their problems? Check.

I don’t want to say that the Framers anticipated none of these outcomes. On the contrary, many, perhaps most of them led to specific warnings from the white men who wrote our constitutions. But in the end, hope prevailed, even in the face of these misgivings.

Hope may be a virtue, but it is not a plan…at least not generally a very good plan. Which is why we now endure a Constitutional order where almost anything, including mass hallucinations about reality itself, can become an exception to the rule of Constitutional black-letter law.

Many of the Framers might not have been surprised at this. But all, I suspect, would have been disappointed.

There are limits to how much a piece of legaleze can constrain a government. When theoretical government diverges from actual government, actual government wins.

We had democracy because we had a militia system of national defense and a sufficiently egalitarian wealth distribution. We had federalism because communication across the nation as a whole was slow, and arbitraging between state legal and tax systems was expensive and difficult.

We have a two-party system because we have First Past the Post elections for our most important offices. No amount of ballot access reform can fix the Two-Party System. Only changing how votes are counted can do that.

Likewise, now that we have fast transportation, social programs are going to gravitate to the federal government as long as there are no walls between states -- physical or virtual. Currently, we do have walls in the form of residency requirements for in state tuition and California's Proposition 13. Otherwise, it behooves one to live in a low tax state while productive and move to a welfare state if one gets sick or suffers bad fortune.

To bring back the Old Republic, we need to reinvigorate the militia spirit and put a damper on tax/welfare arbitrage. My candidate proposal for the former is to replace TSA frisking with a *civilian* Air Deputy system. Have hundreds of thousands of vetted frequent fliers armed with daggers and tasers in return for a small airfare discount. Likewise, have huge state militias ready to guard disaster areas against looters.

The true lesson of 9/11 is that a free society cannot rely on full time guardians in the event of Black Swan events. You need either a true militia or a police state.