The Greasy Dollar: Lubricating the American Slide Into Permanent Inflationary Hell

Can you hear the canary chorus shrieking at the bottom of the oil well?

For almost all of my adult life, at least since 1964, I’ve heard dire warnings that U.S. deficits and rising national debt would result in crippling inflation, bankruptcy, or both. And by 1971, three years after the final (at the time) peak of the DJIA, it began to look as if those warnings might finally come true. The Dow Jones Average began a decade plus teeter-totter between the 500 and 1000 levels, while inflation remained in the plus ten percent range, and much of our industrial plant was either shipped overseas or shuttered outright.

It took the Volker/Reagan tag team hiking interest rates to an unprecedented 20% to finally slay the stagflation beast, and in the process kicking off a multi-decade boom in stock prices that even the dot.com crash at the turn of the millennium couldn’t really dent. As an aside, one of the most notable casualties of that event, the bankruptcy and demise of webvan.com, a company that used the online ordering/delivery of groceries as a proof of concept for their effort to solve the last-mile problem, did put a huge dent in my own personal financial boom.

Shortly after that, souring on my stock-picking abilities, I put my faith in inflation and my remaining nest egg into the purchase of a condo town home in San Francisco, financed at a fixed rate of 5%. I was offered a couple of variable rate adjustable mortgages, but as I happened to be a licensed realtor at the time, I just looked at the lenders and said, “You kidding me?” Turned out to be one of my (few) excellent financial decisions, and while the nominal value of my property plummeted in the wake of the 2007-2008 housing catastrophe, which was really a catastrophe of speculative financialization, good old inflation over the following years restored all the value that had existed at the peak of the housing boom and added considerably more. I cashed out and left San Francisco in late 2016 for my original home state, Indiana, and found a land it seemed inflation had forgotten. At least by San Francisco standards, just about everything seemed dirt cheap to me, probably because it was.

Inflation seems almost like fire. It can be your friend, but it can also turn you into a pile of smoking ashes. It also seems to have as many definitions as the Eskimo have words for snow. It is, we are ponderously instructed by the legendary economist Milton Friedman:

The Real Story Behind Inflation | The Heritage Foundation

Milton Friedman famously said: “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”

For the layman, inflation just means higher prices for the things you buy. Uncle Milton says it only happens when the supply of money is greater than the output of goods to buy with it. Most people assume this means that the only way to get it is to turn on the government printing presses. However, it would be equally accurate to say that if you destroyed a lot of goods along with the ability to make more and replace them, inflation would be the result.

The average person’s formulation of Friedman's dictum would be, “Too much money chasing too few goods,” and either side of that equation can be jiggered with.

To add to the confusion on the matter of inflation (rising prices caused by an imbalance between money supply and available goods) there are three types of inflation.

Inflation: What It Is, How It Can Be Controlled, and Extreme Examples

What Causes Inflation?

There are three main causes of inflation: demand-pull inflation, cost-push inflation, and built-in inflation.

Demand-pull inflation refers to situations where there are not enough products or services being produced to keep up with demand, causing their prices to increase.

This is the “not enough available goods to buy” version.

Cost-push inflation, on the other hand, occurs when the cost of producing products and services rises, forcing businesses to raise their prices.

An example of this would be the result of the US government’s global sanctions warfare which raises the costs of goods and services that have been embargoed or otherwise made scarcer by one side or the other as a consequence. That means that producers who need these goods to make their own products must pay more, which forces them to raise prices as well.

Built-in inflation (which is sometimes referred to as a wage-price spiral) occurs when workers demand higher wages to keep up with rising living costs. This in turn causes businesses to raise their prices in order to offset their rising wage costs, leading to a self-reinforcing loop of wage and price increases.

This is more an addendum than a different type of inflation. It is really only a specific example of the cost of goods rising faster than the money available to pay for them.

So, everybody hates inflation, right?

Not quite. (See my example involving San Francisco real estate).

People who own what are generally called “hard assets” — precious metals, land, commodities, food or food product companies — all do well in times of inflation. You can double the bang for your buck by investing in agricultural land, which is probably why Bill Gates is now the largest owner of farmland in the United States. Highly portable hard assets like fine gemstones are also a traditional backstop against inflation.

There is another big one: governments at every level that tax income even if, adjusted for inflation, the gains don’t actually exist. An increase of your income of 5% when inflation is also 5% results in a net real gain for you of zero. Yet you will still be taxed on your 5% increase.

There are other investments that benefit from inflation, but their principal characteristic is that owning them tends to be the province of quite wealthy people. The One Percent, more or less, although they are popular with The Ten Percent as well. The average American may own a home - at least the part of it the bank doesn’t own, and as such it remains their largest inflation advantage. They don’t mind seeing inflation push their home values up, and probably would get more of it if they could. At least as long as they don’t have to take out a new mortgage in order to buy groceries and gas up their vehicles - and their original mortgage, if not paid off, can’t be adjusted to reflect inflation, unlike their credit cards.

Has Inflation Always Been With Us?

No.

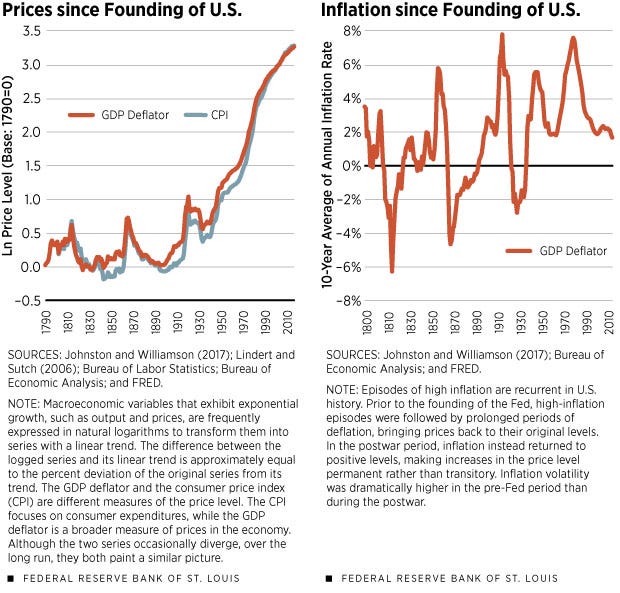

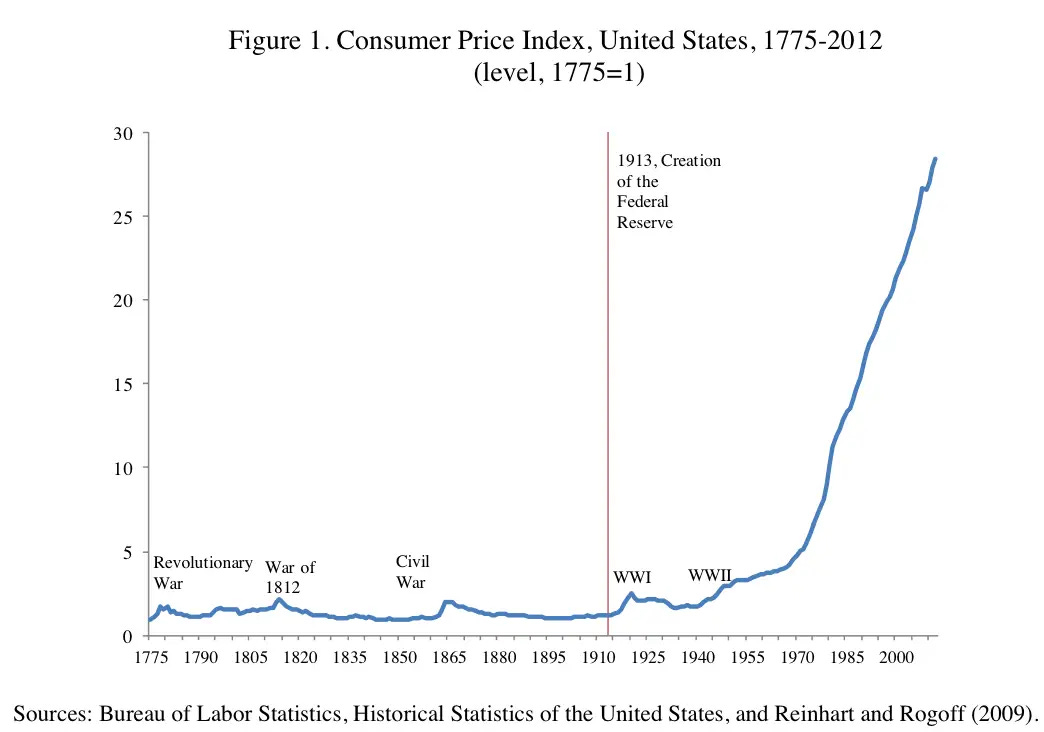

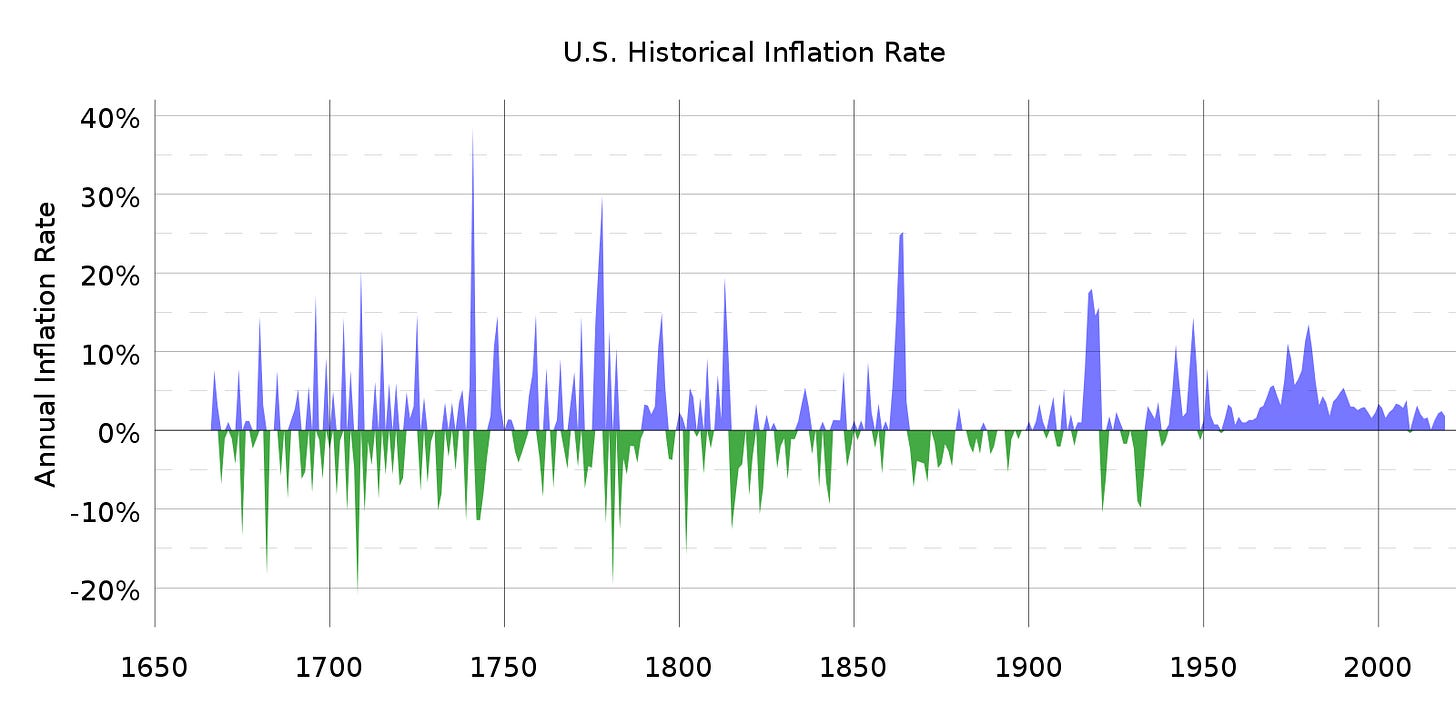

Reflect on these three charts.

What we really need to know in order to understand how much of an issue, let alone a problem, inflation has been throughout American history is how much, over time, net inflation affected the nation and its citizens. Sure, there were periods of inflation, but they were relatively short-lived, and followed by periods of deflation the resulted in a long-term net of close to zero. Remember: if the price of something increases by 100%, it only takes a fall of 50% to return you to the original price. And so, for 150 years, inflation in America was essentially a long-term non-factor.

A quote from the paper in which this chart appears:

It is probable that in 1913, while financial panics were not uncommon, high inflation was still largely seen by the founders of the Fed as a relatively rare phenomenon associated with wars and their immediate aftermath. Figure 1 plots the US price level from 1775 (set equal to one) until 2012. In 1913 prices were only about 20 percent higher than in 1775 and around 40 percent lower than in 1813, during the War of 1812.

In other words, however many goods you could buy with a hundred bucks in 1813, you could buy 67% more of them 100 years later with the same amount of money. That is why, long term, you have to consider the net effects of inflation and deflation combined. And, in fact, net long term net inflation from 1775 until about 1935 was as near to zero as makes no difference.

Why did this happen? The consensus seems to be that a combination of currency backed by precious metals, coupled with the natural effects of laisses faire capitalism and the usual actions of various business cycles, combined to allow inflation to heal itself with deflationary reactions (and deflation likewise). It is no accident that the United States advanced from being basically a small agrarian economy to the largest and strongest economy in the world during that period. It had also become the issuer of the de facto global reserve currency, although the British pound held that nominal role for another ten years before being officially dethroned at Bretton Woods in 1956.

At any rate, things were pretty good, inflation-wise, in America from the time of the Founders up to the mid-1930s. What might have happened then to set off that hockey stick formation on the charts? A lot of people have blamed the Federal Reserve, but remember, it was created in 1913, and not much changed for the first twenty years of its existence. However, in 1933, something more momentous happened.

Whatever the mandates of the Federal Reserve, it is clear that the evolution of the price level in the United States is dominated by the abandonment of the gold standard in 1933 and the adoption of fiat money subsequently. One hundred years after its creation, consumer prices are about 30 times higher than what they were in 1913.

Enter the fine Old New York Dutch hand of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who fully understood about never letting a good crisis go to waste long before Winston Churchill explicated the maxim (and Rahm Emanuel famously stole it). Most people think Richard Nixon took us off the gold standard in 1971, but that’s not the case.

On June 5, 1933, the United States went off the gold standard, a monetary system in which currency is backed by gold, when Congress enacted a joint resolution nullifying the right of creditors to demand payment in gold. The United States had been on a gold standard since 1879, except for an embargo on gold exports during World War I, but bank failures during the Great Depression of the 1930s frightened the public into hoarding gold, making the policy untenable.

Soon after taking office in March 1933, President Roosevelt declared a nationwide bank moratorium in order to prevent a run on the banks by consumers lacking confidence in the economy. He also forbade banks to pay out gold or to export it. According to Keynesian economic theory, one of the best ways to fight off an economic downturn is to inflate the money supply. And increasing the amount of gold held by the Federal Reserve would in turn increase its power to inflate the money supply. Facing similar pressures, Britain had dropped the gold standard in 1931, and Roosevelt had taken note.

On April 5, 1933, Roosevelt ordered all gold coins and gold certificates in denominations of more than $100 turned in for other money. It required all persons to deliver all gold coin, gold bullion and gold certificates owned by them to the Federal Reserve by May 1 for the set price of $20.67 per ounce. By May 10, the government had taken in $300 million of gold coin and $470 million of gold certificates. Two months later, a joint resolution of Congress abrogated the gold clauses in many public and private obligations that required the debtor to repay the creditor in gold dollars of the same weight and fineness as those borrowed. In 1934, the government price of gold was increased to $35 per ounce, effectively increasing the gold on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheets by 69 percent. This increase in assets allowed the Federal Reserve to further inflate the money supply.

In other words, FDR ended the gold standard for the United State currency in a deliberate attempt to foster Keynesian-style inflation, offered and accepted by the left as the sovereign remedy for disinflationary ills. Of course, deep-sixing the gold standard was a rather permanent inflationary fix, while Keynes, obviously with one eye fixed on the metronomic back and forth of inflation and deflation over the previous century and a half, prescribed ratcheting down inflationary stimuli once the deflationary crisis had passed. But that part is always forgotten by national leaders who see permanent inflation as one of a government’s most lucrative and useful piggy banks.

Voila! - inflation had become structurally ingrained in the U.S. economy, a situation that has remained to this day. Eleven years and the most massive example of global warfare in history later, all the big guns had a clambake at a small resort town in New Hampshire called Bretton Woods. For science fiction fans, the resort itself sits at the base of Mount Washington, home of some of the most atrociously awful weather on the planet, a thinly disguised version of which plays a significant role in Julian May’s epic SF series The Saga of the Pliocene Exile. Seems somehow a fitting location for the formal ushering of the English pound into exile from its century long run as the world’s reserve currency - as well as the end of England’s status as the dominant thalassocracy in the western world.

Storm clouds atop Mount Washington above Bretton Woods resort.

Keep in mind that in the years leading up to Bretton Woods, two massively inflationary events took place: First…

…In 1934, the U.S. government revalued gold from $20.67 per ounce to $35 per ounce, raising the amount of paper money it took to buy one ounce to help improve its economy.

As other nations could convert their existing gold holdings into more U.S dollars, a dramatic devaluation of the dollar instantly took place. This higher price for gold increased the conversion of gold into U.S. dollars, effectively allowing the U.S. to corner the gold market. Gold production soared so that by 1939 there was enough in the world to replace all global currency in circulation.

This “dramatic devaluation of the dollar” amounted to effectively inflating the US currency by about 75%.

Sections 5 and 6 of the act prohibited the Treasury and financial institutions from redeeming dollars for gold, inverting the system that had prevailed in the United States since the nineteenth century. Under that system, the government converted paper currency to gold coins, whenever citizens desired to do so. Now, the government converted gold into dollars, regardless of whether citizens wanted to engage in the exchange.

At gunpoint, in other words. The US government has a very long history of stealing gold for its own purposes. In this case it was both to provide a massive inflationary stimulus to an American economy sunk in a deflationary depression while at the same time filling its own coffers with most of the gold in the world. And remember, while foreigners couldn’t sell gold to individual Americans, they were encouraged to sell gold to the American government.

The second massively inflationary event was World War II itself. Wars are almost always inflationary, unless the outcome for a combatant is so dreadful that its economy is destroyed. However, an economy takes a lot of killing to get the job done. Witness the German economic renaissance post WWII as an example. The combination of the two produced the highest sustained period of inflation in US history up to that time. But it was only a taste of what was to come.

At any rate, this was the economic backdrop for the titans of WWII meeting at a ski resort in New Hampshire in 1944 to bury old heroes, crown new ones, and divvy up the Western economic world which, as far as they were concerned, was the only part of the world that actually mattered.

Now here is where it gets interesting.

What Happened at Bretton Woods? | AIER

Harry Dexter White, who led the negotiations for the United States at the Bretton Woods Conference, was a spy for the Soviet Union. He pursued the plan to eliminate the United Kingdom as a financial rival and as a sea power, Germany as a Continental power, and Japan in the Pacific to establish a new Communist world order together with the Soviet Union.

White adamantly denied these accusations, which were never absolutely proven, but given later revelations, including data from the Venona Project, they were probably true.

His counterpart, in a surprising twist, chairman of another of the three major commissions and representing Britain in the negotiations, was the father of the sovereign remedy of inflation, John Maynard Keynes. The two men dueled throughout the conference, but since the U.S. at that point held all the financial cards, Keyes and Britain lost most of the battles. Britain’s day in the global light of the sun that never set was over, and with it its reserve currency and its status as the world’s greatest sea power. It was America’s turn now but saying so only ratified formally what had already been a fact for several years.

Among the accomplishments of Bretton Woods were the creation of two of the pillars of the modern financial system, the International Monetary Fund - a sort of international financial fireman - and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development - probably the most significant part of the World Bank.

Bretton Woods also ratified the U.S. dollar as the global reserve currency, and kept it pegged to FDR’s $35 USD gold price. And everybody else got to peg their currency to the dollar. This made sense because most of the world’s gold bullion was now sitting quietly in the vaults of the New York Federal Reserve Bank on Liberty Street in New York City, with by far the largest portion owned and controlled by the U.S. government. No point in pegging your currency to a metal you didn’t yourself possess.

Most Americans could not today tell you what Bretton Woods was, or what happened there, but it was the birthplace of what, for lack of a better term, can be called The New World Financial Order. It was the best the participants could do to untangle and then buttress against all the tumultuous changes the world had seen since the guns of August finally stopped thundering at the end of the Great War (soon to be succeeded by Great War 2.0).

They tried hard, and many of their creations, like the IMF, the World Bank’s lending arm, and the U.S. dollar’s unassailable status as the world’s reserve currency, have lasted to this day. But all are now starting to crumble thanks to the fourth creation of the meeting at Bretton Woods: An American world built on permanent runaway inflation.

The Rest of the Story

It took a while to get the brave new world of Bretton Woods completely up and running, fourteen years, to be precise, but by 1958, those who steered the American economic state could rejoice that we had reached a permanently high plateau, fueled by the twin engines of the U.S. dollar’s reserve currency status, and the massive power of America’s mammoth industrial base.

Creation of the Bretton Woods System | Federal Reserve History

In 1958, the Bretton Woods system became fully functional as currencies became convertible. Countries settled international balances in dollars, and US dollars were convertible to gold at a fixed exchange rate of $35 an ounce. The United States had the responsibility of keeping the price of gold fixed and had to adjust the supply of dollars to maintain confidence in future gold convertibility.

The Bretton Woods system was in place until persistent US balance-of-payments deficits led to foreign-held dollars exceeding the US gold stock, implying that the United States could not fulfill its obligation to redeem dollars for gold at the official price. In 1971, President Richard Nixon ended the dollar’s convertibility to gold.

And if nothing had been seen of deflation over that entire post-war period, what did it matter? We were shipping the inflation we got instead, along with our automobiles and blue jeans, abroad anyway. Crack open the champagne, boys! It’s party time!

This apotheosis of financial bliss purportedly created by the delegates at Bretton Woods lasted only thirteen years, before it began to break down, unable to bear the increasing weight of its lesser-known creation, unbridled long term inflation in the United States.

The operation and demise of the Bretton Woods system: 1958 to 1971 | CEPR

The Breakdown of Bretton Woods, 1968 to 1971

A key force that led to the breakdown of Bretton Woods was the rise in inflation in the US that began in 1965.

Compared to the historical baseline, the rise actually began some thirty years previously, and was well above that line by 1965.

Until that year, the Federal Reserve Chairman, William McChesney Martin, had maintained low inflation. The Fed also attached high importance to the balance of payments deficit and the US monetary gold stock in its deliberations (Bordo and Eichengreen 2013). Beginning in 1965 the Martin Fed shifted to an inflationary policy which continued until the early 1980s, and in the 1970s became known as the Great Inflation.

Check this chart again.

You won’t find an end to inflation in the early 1980s on it, no matter what the U.S. Central Bank claimed it was doing to control the beast. In fact, the true Great Inflation, which began in the mid-1930s, only accelerated, as it continues to do to this day.

The decision to suspend gold convertibility by President Richard Nixon on 15 August 1971 was triggered by French and British intentions to convert dollars into gold in early August. The US decision to suspend gold convertibility ended a key aspect of the Bretton Woods system. The remaining part of the System, the adjustable peg disappeared by March 1973.

But Nixon wasn’t done, nor was his Dark Architect, Henry Kissinger. The collapse of Bretton Woods, while it might have saved the American gold reserves, threatened the U.S. dollar’s reserve currency status. All that had previously underpinned that status was beginning to look a little shaky, especially with the destruction of the Bretton Woods guarantees that formalized that status. And wolves were beginning to sniff around, most notably Britain and France. Both countries resented the “exorbitant privilege” the U.S. owned by virtue of its status as the issuer of the global reserve currency. Nixon and Kissinger understood that a sweetener was needed. And maybe a stick. They found one.

Dick and Henry’s Excellent Arabian Adventure

Henry Kissinger, at that time US Secretary of State, saw a way to solve the problem. Actually he found a way to solve three problems: the Arab-Israel problem, the oil problem, and the currency problem. He traveled to Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest oil exporter, and negotiated a deal with them to create the petrodollar system. The arrangement had two components:

The US would guarantee the security of the Saudi Arabian regime and agree to sell them the best arms and equipment our military-industrial complex could supply. In exchange, Saudi Arabia would use its position in OPEC to guarantee that all oil trade was denominated in US dollars.

The US would open its markets to foreign investment from OPEC members. In exchange, a substantial portion of surplus oil proceeds would be used to purchase US Treasury debt.

This deal formed the basis of the petrodollar system. The US dollar was now backed, not by its own gold, but by other country’s oil!

And not incidentally, the U.S. was now free to continue exporting its own inflation to the rest of the world via the dollars that spewed from its printing presses in an ever-growing stream. Not really. Nations don’t send paper money to each other. These are mostly just additions of or changes to entries in various ledgers. Just as nations generally don’t trade physical gold, which often sits in the basements of the NY Federal Reserve Bank. Just the ownership labels are rewritten, or the bullion is moved from one vault to another. Otherwise, the gold stays put.

The bottom line is that it is a combination of the status acknowledged at Bretton Woods, plus the reinforcement of that status by the petrodollar deal Kissinger engineered that currently supports the USD’s existence as the only known global reserve currency not backed by a precious metal.

So how, exactly, does the US export its own inflation via its “exorbitant privilege?”

Most simply, inflation is caused by nothing more than an imbalance in which there is a lot more money available to buy stuff than there is stuff available to buy. Which is why printing an enormongous amount of money, which the US has done for decades, while it has consistently produced fewer goods over the same period (we exported our industrial strength right along with our greenbacks), should be extremely inflationary here in America. But it hasn’t been, at least not on the scale the imbalance between what we print and the goods we make would suggest it should be. So why is that?

It’s because those wildly inflationary fake-bucks aren’t actually available here. You don’t have them, so you can’t spend them to buy stuff and thereby drive up prices, thus creating inflation. And that is because, thanks to reserve status reinforced by the petrodollar recycler, that money is in various repositories overseas, being used to buy oil, or sent back to the US to sit in huge hoards of treasury bonds, none of which puts any extra money in Joe Paycheck’s wallet. Sure, we still have some inflation - just look at those charts again - but nothing like what we would have had if the thirty-plus trillion fiat greenbacks we’ve printed up over the last several decades had been allowed to slosh around in pocketbooks here in America.

Yet here we are, with the inflation sirens going off again, as if the last few trillion we printed up were somehow intrinsically more inflationary than the first thirty trillion. But they aren’t. Phony money is phony money. But something has changed, and that is the global environment in which the last trillion or three was tossed into the gaping global hopper. Let me count the ways.

In the name of fighting a senseless war in Ukraine, we have launched a much larger sanctions war which, as with Samson pulling down the temple, is hurting us and our friends at least as much as it is hurting our enemies, and probably more.

We have also stolen (we like to say confiscated) a great deal of foreign wealth stored with us for safekeeping. This has caused many others who also store wealth with us for safekeeping to become nervous about the safety part of that equation, and to seek other arrangements. China, for instance, is using some of its huge store of dollars to buy a huge pile of gold.

It is said that to replace a reserve currency, you must first answer the question, “With what?” The current actions of the US, along with the various threats it has made against Russia, China, and any who dared to cooperate with them, has accelerated the creation of a specific what, mainly a group bound by various alliances, treaties, and other agreements, both political and economic/financial in nature, that can loosely be called the Eurasian League. One of its stated goals it to unseat the United States dollar from its unchallenged status as the world's reserve currency.

This league either formally, or informally, includes the world’s biggest economy (PPP), two of the three most powerful militaries on the planet, two of the three largest oil producers, 40% of the world's population, enormous quantities of natural resources, and 35% of the world land mass.

And while there is no argument that the U.S. and its allies are by far the richest grouping in the world, all the trends between these two show Eurasia growing and the western powers faltering.

Which brings us to the current state of play. Just about all of the markers that made America fit to exercise the “exorbitant privilege” of owning the world’s reserve currency are in the process of collapsing or have collapsed. And now there is real, if yet still nascent, competition for the role. Does the world still want the U.S. dollar? Does it still need the U.S. dollar? The answer to both is up in the air. Absent anything else, sheer inertia might be enough to keep things rolling along for a while. But certainly one of the last things that helped to hold this rickety ship together, the petrodollar trade, may very well be on its last legs. Joe Biden promised to make Saudia Arabia a pariah on the world stage. Instead, Joe is looking a bit pariah-ish these days, what with being comepletely shut out of the new agreements between Iran and KSA brokered (successfully) by China. Not to mention The Kingdom no longer holding the gates against the sale of oil denominated in currencies other that the USD. If this all results in the collapse of the Great Greasy Petrodollard,, the Next Big Inflation could make everything that has gone before look like a happy stroll about Mount St. Helens just before it blew its stack.

Forgot to mention: Like Communism, true Keynesian economics has never been tried, and for much the same reason. Each fails to take into account human nature. Real humans in a "communist paradise" will grub power and hoard resources whenever given a chance. Real humans running a "Keynesian paradise" economy will deficit spend when there's an excuse such as a recession or a war but they won't reduce spending below revenue in order to pay down debt and build up a surplus.

[International Monetary Fund - a sort of international financial fireman]

Some would say that the IMF is a fireman in the Fahrenheit 451 sense.

[meeting at a ski resort in New Hampshire in 1994]

Typo, I think. 1944?

I knew most of the stuff about Breton Woods and its piece-by-piece dismantling. The American negotiator being a commie spy had passed me by. Can't say as it surprised me, though. A sizable fraction of the US government from the 1930s to today have worked for the USSR, the PRC, or other masters aside from the American people and Constitution.

re the federal reserve, I differ somewhat with you. I'd say that it's doing exactly what was intended since 1914, serving as the master control in the hands of people who don't know what they're doing. Its legality was dubious from the start but its influence was hobbled for its first two decades, until the checks and balances of backing currency by gold were removed.