“Yes, you take a size medium, sir.”

After I recently lost 102 pounds - about 42% of my total bodyweight - I discovered I had some major issues with clothing sizes in my wardrobe. First, you should probably understand the nature of my clothes. They are old.

My dad originally taught me how to dress, when it came time to do that. I didn’t really have many opinions about my own clothing until I got into my junior high years, but in those days parents, despite all the whinging from GenX on how abandoned they were, didn’t pay much attention to their kids. Moms pretty much handled the clothing decisions, and most, including mine, were more interested in trying to keep us shod and decently covered during a time when most of us kids were growing out of stuff faster than it could be manufactured. Or so it seemed. As a consequence, nothing ever really seemed to fit. Pants were too long and had to be folded up at the bottoms - not cut or hemmed, because you’d need that length later - shirts were always a size or two too large (Everything was - Hey, you’ve got a chicken neck look going there, kid), and as for the one obligatory Sunday church and school suit, well, it was just sad. You always ended up looking like either a scarecrow or a sausage.

But we - by which I mean we guys - didn’t really care, because clothing was functional, and style, and even more so, fashion, simply wasn’t a big concern. This was all going on during the first of the Post-war decades, when everybody was recovering from looking a bit tatty anyway. By the time I turned 14, it was made plain to me that I would be going off to boarding school in the east soon, at which point my father took a totally unexpected interest in my heretofore entirely ignored manner of dress.

One fine summer Monday morning, my dad woke me up, told me to get dressed “in something respectable, no blue jeans, please,” and then, after a short inspection for respectability, put me into his car, and off we went…to Chicago.

I had high hopes that we would visit the Lionel Train store, located in the Hilton Hotel, but when I mentioned the possibility, dad said, “no, at least not first. If there’s any time left after we finish, maybe. We’ll see.” Dad liked a good Lionel himself, as we both knew.

“After we finish what?”

“Buying you some clothes.”

“What?”

He sighed. “Bill, you’re going off to school this fall. You will no longer be a child. You’ll be a young man, living with other young men, and you need to dress like it.”

I was utterly mystified. I had no idea what he was talking about. I soon found out when he found a parking space on Michigan Avenue in front of the Athletic Association and led me around the corner to a clothing store with a sign that announced “Brooks Brothers.”

I’d always vaguely known that my dad bought clothes there, although I’d personally never seen the place. It was one of the sacred adult male mysteries. I began to feel I might be on the edge of some sort of revelatory experience. As it turned out, I was.

We paused before entering and my dad looked me in the eye. “Son, I’m going to give you two pieces of advice that have stood me in good stead my whole life, and I hope they will do the same for you.”

He thought for a moment, then nodded, and said, “When it comes to clothes - in fact, when it comes to most such things - you should always buy the best quality you can afford, take good care of it, and use it for the rest of your life or until it falls apart, whichever comes first.”

He opened the door and offered his second piece of advice. “When it comes to clothing, you can’t do better than Brooks Brothers.” The second wasn’t entirely true, but close enough. In those days Brooks would even make you bespoke clothing in their custom department.

Anyway, in we went. He caught the eye of a clerk (who recognized a Brooks Brothers suit when he saw one), and told him, “This young man is going off to school in the fall. He needs whatever is suitable.”

The clerk eyed me up and down, nodded, and said, (to my dad, not me), “Of course. What were you thinking for the young gentleman?”

First time in my life anybody ever called me a gentleman.

“He’ll need a good suit, dark gray or navy, a navy blazer, half a dozen dress shirts, button down, three white, three light blue, three sport shirts, four pairs of khakis, a pair of dress shoes, black, a couple of belts, socks, underwear, a dark overcoat, a raincoat, and the rest of the usual haberdashery you think appropriate. He can pick the ties and sport shirts, as long as they are also appropriate.”

“Dad, don’t I get to make any decisions about what I’m going to be wearing?”

He smiled faintly. “Of course. Whatever you pay for here, you can decide on.”

So much for that.

The clerk said, “Well, son, let’s get your measurements.”

“Huh? What for?”

“Once we have your measurements on file, you can just call us up and tell us what you need, and we’ll make it for you.” He glanced at my dad. “Where will he be going?”

“The Hill School.”

“Ah. Then we’ll see that our New York store has his measurements as well.”

Dad nodded.

“He’s a growing boy, so we will cut his garments to take that into account. Plenty of room to let things out.” He turned to me. “If you find something no longer fits, just bring it to one of our stores and we will alter it for you. And change the measurements we have on you too.”

And so I received my first lessons on dressing well and, I suppose, living well also. Dad’s first piece of advice, which I have followed, and which has, indeed, served me splendidly, I commend to you if you don’t already know it. By the end of my prep school career I had outgrown even the ability of the Brooks tailors to fit me into my original wardrobe, but I do still have two of the ties. And all of my dad’s old ties, two of his hats, and so on.

The oldest Brooks suit I have is a charcoal number with a fine pinstripe in a size 40, more or less, much altered over the years. It actually measures out to something between a 38 and a 40. I bought it in the latter 1960s, and kept it despite some unfortunate ventures into fashion involving bell bottoms and other such crimes in the following decade. It remains in excellent shape and I’m looking forward to wearing it once the weather around here turns cool.

All of this is in aid of making the point that I own, and wear, a lot of old clothes, which puts me in an excellent position to opine more or less knowledgably about the sizes of these things over the years.

I had just turned 18 in 1964, and most of my growing was done. I could pretty much depend on a weight stabilized in a range between 140 and 150, which I maintained without effort while eating anything I damned well pleased and as much of it as I wanted, although in another 15 years I would begin to pay dearly for my sins.

I wore a 15 1/2 x 34 dress shirt, size 38 suits off the rack, 30x30 pants, medium in other shirts and sweaters, and that didn’t change for a good while, nor did clothing that complied with those measurements vary much from store to store in the way they fit. I might need a little nip or tuck every once in a while, but not much and not often.

And I never threw any of this stuff away unless there was absolutely no other alternative.

Which is why, after I had dropped the aforementioned 102 pounds, I hauled out everything I’d been unable to wear, and tried it on. That turned into a real eye-opener. Just about everything I’d bought in those sizes post 1990 was way too big, in some cases literally cavernous. That old Brooks suit from the sixties fit like a glove, though, and most of my older good shirts were still okay. The bespoke pieces (personally made for me) I had were good as well, as they were fitted to the old skinny me.

But as for the rest? Pretty much everything needs to be taken in, and in some cases, taken in a lot. What on earth had happened? Just to make sure I wasn’t hallucinating I went to the local Goodwill, and picked up a couple pairs of disposable trousers, a suit, and some shirts in the 15.5x34 range. No, it wasn’t either my imagination or my delusion. All of them were much bigger on me than my old clothing in the same sizes.

I could only conclude that, for some godawful reason, the people who now make men’s clothes have unanimously decided to lie about their sizing. And, upon further investigation, that turns out to be precisely what has happened. And not just to men. Women have it even worse.

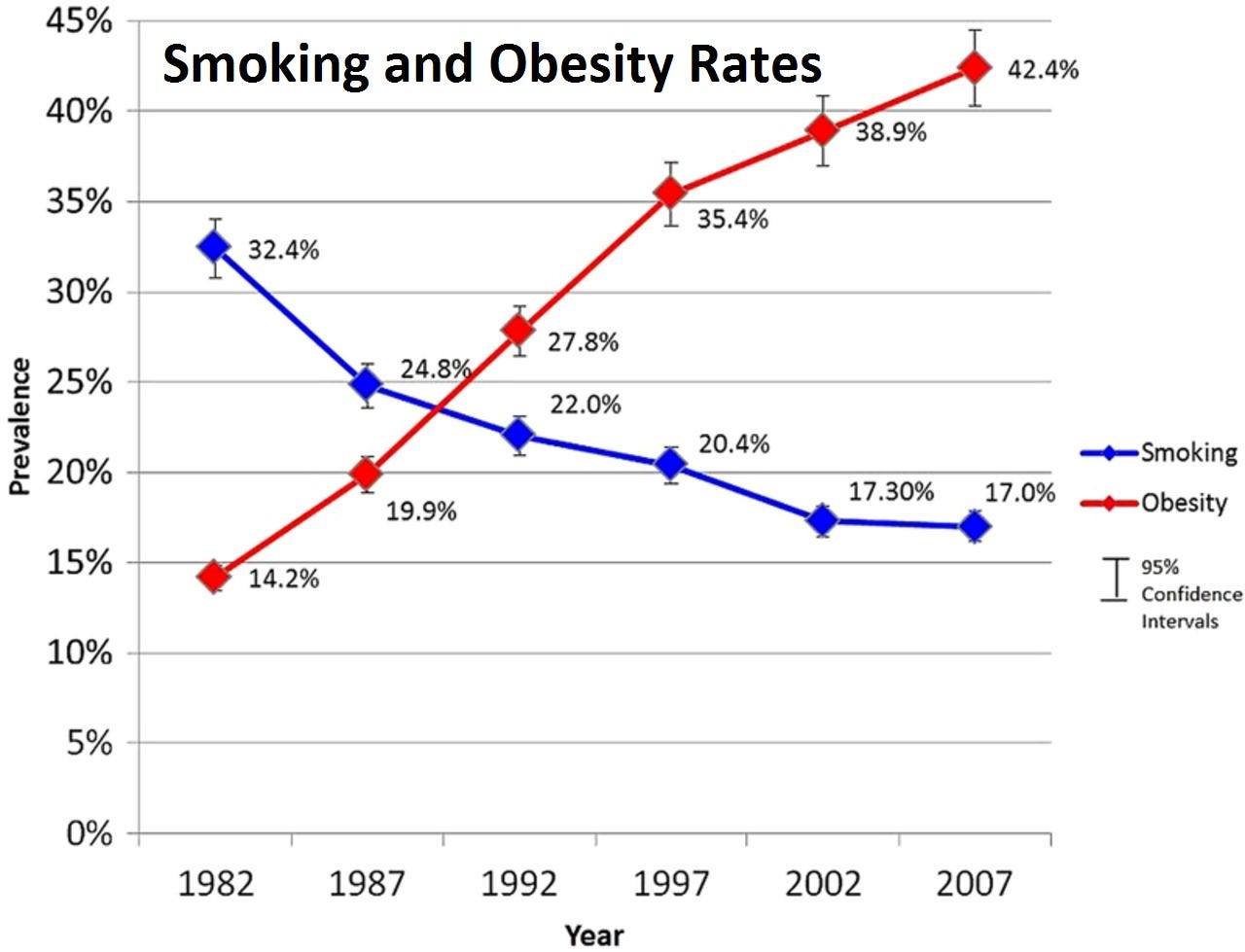

As so many of the horrible things in our current culture do, this had its origin in the 1970s. The first thing we did was to begin to stop smoking.

And the second thing we did was to begin to follow the dietary “Food Pyramid” created by George McGovern’s Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs, which emphasized a low fat, carbohydrate-heavy diet as being a healthy goal for all Americans.

And just like that, Americans started getting fatter. And fatter. And fatter.

The average woman today weighs as much as the average man in 1960

Upon which, mirbile dictu!, the clothing industry responded by lying its head off.

Although those in the industry take great umbrage at the term “vanity sizing,” (and I can only imagine the rage at my charge of “lying their heads off”) the truth is that they have steadily changed the meaning of their sizes in order to appease differing segments of the garment industry, from the retail and (more important, wholesale) buyers, clothing designers, and various other stakeholders, for a purported plethora of reasons - which really boil down to just one.

Women are affected most by vanity sizing, or, more accurately, size inflation. This is most likely due to prevailing notions of female physical attractiveness and the many clothing measurements that go into displaying it to the satisfaction of the female customers involved. But men are not immune to the issue either:

Although more common in women's apparel, vanity sizing occurs in men's clothing as well. For example, men's pants are traditionally marked with two numbers, "waist" (waist circumference) and "inseam" (distance from the crotch to the hem of the pant). While the nominal inseam is fairly accurate, the nominal waist may be quite a bit smaller than the actual waist, in US sizes. In 2010, Abram Sauer of Esquire measured several pairs of dress pants with a nominal waist size of 36 at different US retailers and found that actual measurements ranged from 37 to 41 inches.[15] The phenomenon has also been noticed in the United Kingdom, where a 2011 study found misleading labels on more than half of checked items of clothing. In that study, the worst offenders understated waist circumferences by 1.5 to 2 inches. London-based market analyst Mintel say that the number of men reporting varying waistlines from store to store doubled between 2005 and 2011.[16]

Are Your Pants Lying to You? An Investigation

So I immediately went across the street, bought a tailor's measuring tape, and trudged from shop to shop, trying on various brands' casual dress pants. It took just two hours to tear my self-esteem to smithereens and raise some serious questions about what I later learned is called "vanity sizing."

Your pants have been deceiving you for years. And the lies are compounding:

The pants manufacturers are trying to flatter us. And this flattery works: Alfani's 36-inch "Garrett" pant was 38.5 inches, just like the Calvin Klein "Dylan" pants — which I loved and purchased. A 39-inch pair from Haggar (a brand name that out-testosterones even "Garrett") was incredibly comfortable. Dockers, meanwhile, teased "Leave yourself some wiggle room" with its "Individual Fit Waistline," and they weren't kidding: despite having a clear size listed, the 36-inchers were 39.5 inches. And part of the reason they were so comfy is that I felt good about myself, no matter whether I deserved it.

However, the temple for waisted male self-esteem is Old Navy, where I easily slid into a size 34 pair of the brand's Dress Pant. Where no other 34s had been hospitable, Old Navy's fit snugly. The final measurement? Five inches larger than the label. You can eat all the slow-churn ice cream and brats you want, and still consider yourself slender in these.

Now, there are those within the garment industry who will plead complete innocence, and deny that “vanity sizing,” per se, even exists.

Apparently, anyone who wears clothes is a sizing expert

This is what consumers think but vanity sizing is a myth. We are simply too busy putting out product to even try to figure out how to manipulate consumers or massage their egos with everything we have going on. Minimally, if we were concerned with sizing to ego, there would be instruction and advice in the trade media — to include textbooks and even seminars — on how to do it. I’ll save you a search, there is none.

The sizing discrepancy you observe is better described as size inflation. Sizing normalizes to the mean. If this were not true, we’d still be making clothes to fit people in the mid-1800’s. But then if we did, we would have gone broke because nobody could wear them. I don’t see anyone complaining that doorways and seats are larger but these are also sized to the mean. We have to change our sizes based on average sizes (and) due to the way fabric allocation costs are calculated. If you don’t want sizes to change (to match increasing consumer girth) then everyone needs to go on a diet.

It’s amusing to pick apart the intellectual shortcomings of the argument offered by this industry “insider expert,” which boil down to, “As our customers got fatter, we fattened our sizes to avoid pricking their tender vanity, though that’s not “vanity sizing,” but what the whole effort really is is an attempt to deny reality. And that is the dangerous downside to the whole thing.

“But it’s just clothes,” you protest. “What’s so dangerous? It’s not like it’s a life or death matter.”

Unfortunately, it is. Which is a problem, or, rather, part of a larger problem involving obesity in America today.

First, one must understand that obesity and, to a lesser extent, significant overweight, is a killer on a grand scale. (I’ve discussed this fairly thoroughly elsewhere). And so anything that encourages obesity is a public health problem. If you, personally, happen to be obese, it becomes a contributor to your personal health problems. Just as I excoriate much of the American medical establishment for clinging blindly, ignorantly, and arrogantly to the long-discredited “calories in, calories out” paradigm for both explaining obesity, and, worse, treating it - or as is the actual case, not treating it - I have little use for other stratagems, like vanity sizing, which also do nothing to improve matters on the issue and, indeed, make it worse.

“But what are we to do?” wail the garment industry experts. “Our clients get fat, so we must change our sizes to reflect that!” Actually, that is precisely the opposite of what they are doing. They are changing their sizes to cover up the fact that their clients are getting fat. Which, I suppose, makes a certain sort of twisted sense since clothing’s initial purpose was simply to cover the human body and protect it from the elements. Now, however, we attempt to use it to protect us from reality.

Inside the fight to take back the fitting room

By the end of World War II, those factors—alongside the rise of advertising and mail-order catalogs—had sparked a consumer revolution, both at home and abroad. Made to measure was out. Off the rack was in.

And sizes arrived. In the early 1940s, the New Deal–born Works Projects Administration commissioned a study of the female body in the hopes of creating a standard labeling system. (Until then, sizes had been based exclusively on bust measurements.) The study took 59 distinct measurements of 15,000 women—everything from shoulder width to thigh girth. But the most consequential discovery by researchers Ruth O’Brien and William Shelton was psychological: women didn’t want to share their measurements with shopping clerks. For a system to work, they concluded, the government would have to create an “arbitrary” metric, like shoe size, instead of “anthropometrical measurement[s].”

So it did. In 1958, the National Institute of Standards and Technology put forth a set of even numbers 8 through 38 to represent overall size and a set of letters (T, R, S) and symbols (+, —) to represent height and girth, respectively, based on O’Brien and Shelton’s research. Brands were advised to make their clothes accordingly. In other words: America had research-backed, government-approved universal sizing—decades ago.

But by 1983, that standard had fallen by the wayside. And experts argue it would fail now too, for the same reason: there is no “standard” U.S. body type.

Ah, yes, the self-interested garment sizing experts with no axe to grind, of course. And of course, that argument is bullshit of the purest ray serene. There has never been a “standard U.S. body type,” and there never will be. But sizes are not intended to measure body types. They are meant to provide a reasonably objective guide the consumer can use to select clothing that will fit their bodies.

Universal sizing works in China, for example, because “being plus-sized is so unusual, they don’t even have a term for it,” says Lynn Boorady, a professor at Buffalo State University who specializes in sizing.

Universal sizing works in China because the Chinese are an eminently practical culture not much given to pulling the wool over their own eyes. If they see a fat Chinese person, they don’t think, “My goodness, is that some other sort of new species, some strange offshoot that requires a plus-size measurement?” No, they don’t. They think, and quite often say, “Hey, you are a fat person.”

But America is home to women of many shapes and sizes. Enforcing a single set of metrics might make it easier for some of them to shop—like the thinner, white women on whom O’Brien and Shelton based all of their measurements. But “we’re going to leave out more people than we include,” Boorady says.

More horseshit. What this expert is trying to peddle is the notion that fat people - because that is what we are talking about, just as when we say “climate change” we really mean “global warming", require special “fat sizes” designed to assure them they aren’t really fat. And if we don’t give them that, then they are “left out.”

A Chinese friend in San Francisco, on observing a particularly spectacular version of male obesity waddling into the Abercrombie & Fitch on Market Street, said, “I don’t think that store carries anything in his size.”

“Yeah? What size is that?”

“Extra extra fat.”

This is all craziness. Humans have always been different sizes and shapes. They’ve also been different IQs, different heights, and so on. Do we change how we measure someone’s height because they are very short, and pointing that out might make them feel bad?

Well, given the current cultural taboos on hurting anybody’s feelings by pointing out realities that make them uncomfortable (actual violence, you guys!), making such a change wouldn’t actually surprise me.

But here is the devastating response to all the reality-bending horseshit about clothing sizes:

I enjoyed many of these pants, as I mentioned, but I'm still perturbed. This isn't the subjective business of mediums, larges and extra-larges — nor is it the murky business of women's sizes, what with its black-hole size zero. This is science, damnit. Numbers! Should inches be different than miles per hour? Do highway signs make us feel better by informing us that Chicago is but 45 miles away when it's really 72? Multiplication tables don't yield to make us feel better about badness at math; why should pants make us feel better about badness at health? Are we all so many emperors with no clothes?

The mind-screw of broken pride aside — like Humpty Dumpty, it cannot be put back together, now that you know the truth — down-waisting is genuine cause for concern. A recent report published in the Archives of Internal Medicine found that men with larger waists were twice at risk of death compared with their smaller-waist peers. Men whose waists measured 47 inches or larger were twice as likely to die. Yet, most men only know their waist size by their pants — so if those pants are up to five inches smaller than the reality, some men may be wrongly dismissing health dangers.

But vanity waist sizing is so entrenched, it couldn't possibly be changed overnight, at least not without a government mandate.

Once upon a time, as I noted above, it was a government mandate. Well, not exactly a mandate, but a government approved and suggested method of standardizing measurements and sizes, and if we learned nothing else during the Covid interregnum, we learned how easily “suggestions” from our government can become life-changing, or destroying, mandates.

I’m not going to suggest a return to that, although publicizing those standards couldn’t hurt anything except feelings, arch-crime though that might be.

However, the online retailers are coming up with something that seems to work fairly well. They mate sizing with measurement. This is especially thoroughly done by retailers at the two gigantic sites that market Chinese goods to both Chinese/Asian markets, and US/Western markets. Here is Temu.com:

Combining the two, one can discern that if your waist size it between 35.9 and 37.8, you are a size XL or 36 in US-speak.

It makes sense that online retailers would be in the forefront of attempting to the actual measurements of garments, since they spend billions every year on paying return shipping on purchases that don’t fit their customers.

This still may be a hard sell for many US retailers, though, for reasons of pure vanity and, of course, profit. Some of the vanity comes from a perhaps surprising corner, though.

Karl Lagerfeld’s long history of disparaging fat women

The truths that went unspoken in the industry — that designers are reluctant to make clothes for larger women because they don’t want larger women wearing them, or that they refuse to hire larger models because they think people don’t want to see them — came out of Lagerfeld’s mouth explicitly. Though he was one of the few who felt strongly enough to say it (and occupied a uniquely untouchable status), he surely wasn’t the only fashion designer who didn’t want larger women wearing their clothes: The industry itself is practically built around this philosophy.

And perhaps not so surprising. Fashion and couture designers like to think they are creating beauty when they design garments, and since they have eyes, it is difficult to convince them that something that is manifestly unbeautiful actually is.

Recently, I saw an image of two women walking down the street. Both of them were wearing a slightly different iteration of the same outfit: high-waisted, knee-length shorts with graphic T-shirts tucked in, and a pair of chunky sneakers. The look is trendy; a perfect encapsulation of the pared down, vintage-inspired aesthetic embraced by GenZ TikTok influencers who seem to take style cues from teen movies released 25 years before they were born. It is, as the kids say, a vibe. The women’s heads are cropped from the photo, leaving them unidentifiable. Based on the trendiness of the clothing alone, I’d have mistaken them for a pair of off-duty models, were it not for one key physical characteristic: the women in the picture are fat.

It is not my intent to denigrate fat women. I’ve been fat many times. It is a miserable, often painful, depressing, and absolutely unhealthy existence. I’ve been fighting my weight for going on 45 years. But in no way would I ever try to convince anybody I was handsome in that state. My “thin wardrobe,” which I never jettisoned (hope springs eternal) was very good looking. My one tent-like blazer, and my everyday balloon-like sweatpants and size XXL tee shirts were not. Nor would I expect Brooks Brothers to consider me as a model for their clothing. After all, one of the definitions of model is, “an example for imitation or emulation.” Another is “archetype,” which means “a perfect example.”

Nor does taking what was once a size 00 or XS and turning it into a size 12 or XXL while still calling it by its original nomenclature change the reality of things. Not even if the “fat is beautiful” crowd demands it at the top of its lungs.

This madness is partly our own fault. Studies have shown that shoppers prefer to buy clothing labeled with small sizes because it boosts our confidence.

By lying to us - or permitting us to lie to ourselves. And that is the crux of the matter. As long as we demand that reality reshape itself to make us feel better about ourselves, this problem will continue…because we want it to continue.

My hunch is that it will only cease to be a problem when science finds a way to let us be the size we want to be. Given the choice - be honest now - how many of you reading this would choose to be overweight or obese? You don’t have to tell me, but you can whisper the answer in your own mind - and it would most likely universally be, “Not me.”

We aren’t, as far as I know, working on how to make short people taller, or vice versa, but the biggest complaints Americans currently express about their body sizes involve their weight, and the large majority of those involve being overweight.

Help is here for that, and more, and better is on the way. I don’t expect “vanity sizing to be much of a problem sooner than you might think.

Try being Me Bill... 6'4 and down to 319 (from 342, Yay Me!) but even when I'm at my 'smallest' I still need a 4xl-Long. Buying clothes at DXL sucks too, as I have to pay a premium... never mind dress shirts (22.5-23 inch neck anyone?) At least I still have all my 'thin' clothes when I got waaaay down to 265 (unhealthy for me I found out later). Optimal weight according to my doc(s) is 290-300 +/-... I got about another 20+ pounds to go. And BTW Congrats on the loss man! 42%+/-? Damn son! Good stuff!

Unfortunately we are also on the way to having to also change the definition of IQ, now if you have an IQ of 80 or less you are really smart, and unique, and must be able to work at NASA or whatever else your dreams dictate.

Of course, NASA shouldn't impose any tests because that would leave people out, and that would be a terrible injustice, or looked at another way, not letting these people in, would be a greater injustice than letting these people in and the rocket crashing in some suburb, because it's not even going to crash on the Moon ..